By Matt Wilson

RDA co-chair Colin Nicholson, NT countryside manager Matt Wilson and RDA vice chair Liz Hattan at the AGM

The speaker for this year’s River Deben Association AGM was Matt Wilson, countryside manager for the National Trust for the Suffolk & Essex Coast. His subject was Conservation and Climate Change: his topics were varied, reflecting the varied nature of his responsibilities in this area.

Matt’s title is countryside manager – and that gives him a wide remit, which he’s still exploring. He’s already spent 25 years working in Local Government, within green spaces and blue spaces including for Essex County Council, the London Borough of Barking & Dagenham, and Exmoor National Park authority. Now, with the National Trust for the last 2 and a half years, he has a team of Rangers (currently six) who undertake the practical management and wildlife monitoring on the ground while Matt’s remit is slightly more strategic. He has a particular interest in developing partnership work with other local conservation and environment groups, working at a landscape scale. The area for which he’s responsible runs from Northey Island on the River Blackwater in Essex, to Darrow Wood, over the Suffolk / Norfolk border.

The National Trust is a fascinating organisation to work for, championing ‘Nature, Beauty, History: For Everyone, For Ever.’ It was founded in 1895 and has thus been in existence for 130 years. It’s the biggest conservation charity in Europe. The numbers are astounding. 250,000 hectares, 500 historic houses. 780 miles of coast. 16,000 members of staff. 61,000 volunteers. 1500 tenant farmers. The National Trust (with the National Trust in Scotland) is the nation’s largest farm owner and 90% of its sites are free to enter.

The Trust has recently announced its ten year strategy running from 2025 to 2035:

- Restore nature, not just on NT land but everywhere

- End unequal access to nature, beauty and history

- Inspire people to care and take action

- Renew ways of working in a fast-changing world

Matt then spoke briefly about some of his main areas of responsibility and some of the sites

Northey Island:

This was gifted to the National Trust in 1978 with its farm. It’s the single largest block of salt marsh in the estuary and also includes productive land. This is used for grazing and hay. The rest is creek and salt marsh.

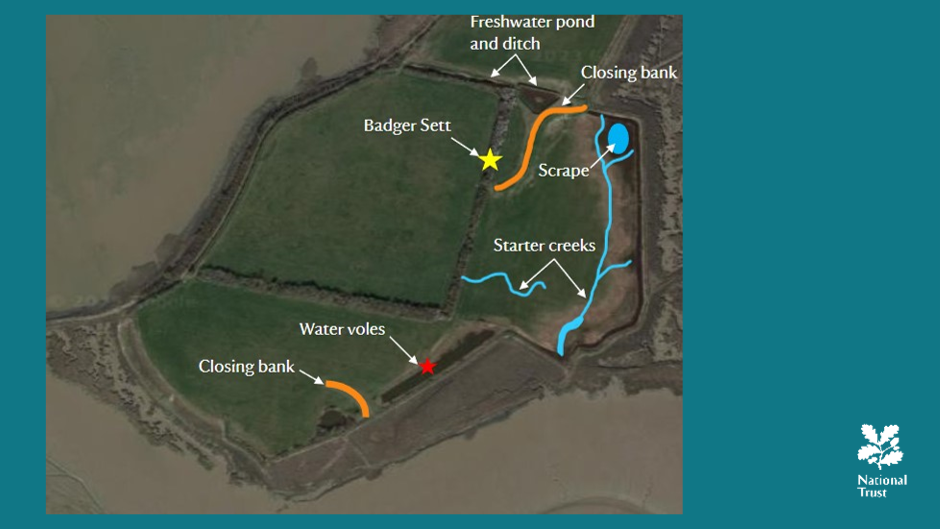

The NT needed a coastal adaptation strategy for the site, especially as it looked at current and predicted sea level rise. Like the Deben, it’s a SSSI (Site of Special Scientific Interest) and is particularly important for overwintering birds as well as waders and water fowl all year round. Matt described various attempts to protect and also to realign the land, particularly focused on the areas of salt marsh which were being scoured out by tidal wave action. Salt marsh is vital for carbon capture. Protective walls around the island had been breached but the water was left with nowhere to go, particularly during storm events, scouring the marsh and leaving only hummocks. Many species were unable to migrate inland due to the walls and were losing their habitats in a process known as ‘coastal squeeze’. The aim was to redirect wave energies and create more habitat with natural flood management techniques. In 1991 removing a section of the seawall helped with dispersion of the energy and therefore allowed the salt marsh to regenerate.

The most recent realignment in May 2023, in the ongoing response to rising sea levels and more frequent storm events, removed 200m of seawall, reduced the height of a further 40m section of seawall and established a new creek system. Higher tides now flow into this land through a breach. More silt is being naturally deposited making new saltmarsh. New plants are moving in and juvenile fish come in and out on the tide.

The annual dredge from Maldon harbour has been used on-site since 2016 to repair other areas of Northey Island saltmarsh, stabilising the sea walls, making them wider and shallower. Making a shallow slope offers the water less chance to to scour after over-topping by the tide as the energy is dissipated. Slowing down the waves reduces the erosion risk giving saltmarsh plants a better chance to move in and stabilise.

Another upcoming project involves three Thames lighters which are about to be positioned to plug a gap in the river wall on the eastern side of the island and create an artificial roost ‘island’. This is a new development – the first time lighters have been used in this way.

Northey Island is open to visitors via a tidal causeway from April to September.

Sutton Hoo:

This 110 hectare site was donated to the National Trust in 1998. 25% of it is woodland. Nine species of bats have been found on the site, which is half the UK species. It’s also a valuable site for wild flowers and for invertebrates, which provide food for both bats and birds. The woodland was previously a pheasant shoot but has been brought back in hand over the past 6 years. Coppicing, the oldest form of sustainable woodland management, has been reintroduced. This ensures that the trees get more dense as they’re cut down. There’s a particular focus on encouraging the natural regeneration of broad leaf trees.

The wood is processed on site and used in a variety of ways, including the site’s fencing needs to protect young growth from deer and rabbits. Benches and tables, finger posts, seats and sculptures are all made on site.

Matt hopes to create more habitat down the western side of Sutton Hoo and increase diversity. There is opportunity for salt marsh restoration and reedbed management, as well as restoring an old wildlfowling pond and improving visitor access to look over the inter-tidal mud for wildlife.

Dunwich Heath:

This was acquired in 1968. It extends over 95 hectares and is a rare habitat of lowland heath, meeting cliff and coast. It’s important for invertebrates, bats and birds.

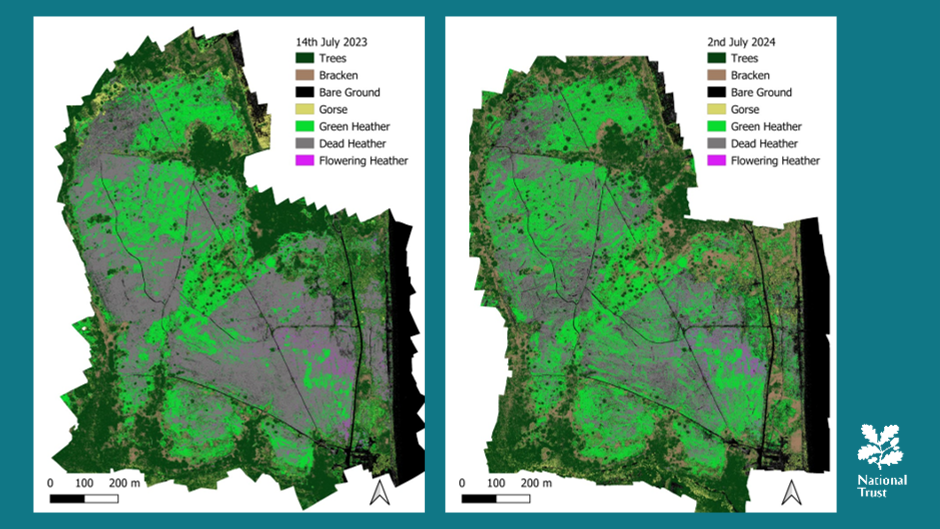

‘I really see the impact of climate change at Dunwich’, said Matt. The 2022 drought really hammered Dunwich and it lost 60% of its heather. It’s also a fire risk. How bad is it now? The drone survey after 2023 showed 60% die off. Some new growth (perhaps 10-11%) was evident in 2024, particularly after a period of heavy rainfall but the heath is still largely brown despite a policy of active heathland management to encourage new growth. The team will be repeating the drone survey in 2025 and in future years to monitor recovery.

Orford Ness:

The National Trust owns 900 hectares on Orford Ness but not all of the site. It has a complicated history. The iconic buildings were AWRE (Atomic Weapons Research Establishment) laboratories, although much of the equipment was removed by the MoD during its decommission. It still remains an important Cold War site and includes Listed Buildings and Scheduled Monument. However, the NT are allowing natural decay and this is intentional though an unusual approach for the National Trust. The buildings and structures were already in various states of dereliction when the National Trust acquired it, and a large number were well beyond a state where they could be authentically repaired. For this reason, the National Trust has adopted a policy of curated decay, where many of the buildings, including the iconic ‘pagodas’, are maintained as ruins in the landscape, with minimal or no intervention to prevent or hasten their decay.

Environmentally, Orford Ness is one of the most highly protected sites in the East of England. It’s a vegetated shingle area, larger than Dungeness and also has reed beds, saline lagoons, salt marsh and grazing areas.

The National Trust acquired the site for its environmental rarity. It’s a dynamic and changing site, because of its coastal nature and particularly the vegetated shingle, formed over centuries through natural wave action. It has 140 species of lichen as well as varieties of spiders and beetles only found in shingle. In 60 to 70 years, the pagodas may be gone. It’s not possible to create vegetated shingle artificially. Once it goes, it’s gone.

The seal colony on Orford Ness has been there since 2021. One of the ranger team was doing a usual post storm check along the beach – because marine litter and sometimes ordnance get washed up. Instead he found 200 seals. It’s thought they had come from Horsey Gap, on the Norfolk coast, north of Great Yarmouth. That first year they had 25 pups, the first to be born in significant numbers, and the following winter they returned and had pups again. More adults come every year; over 500 in 2023 and 600-700 in 2024. Last year (2024) they had an estimated 228 pups.

Matt’s advice is to stay away from seals. Male seals, in particular are three times human weight and are predators. They are the largest land mammals in the UK — larger than red deer — and they have the same dentition as lions (though on a smaller scale!). The bacteria in their mouths can give “seal finger”, which is like tetanus. Matt and his staff all do seal training just in case of need. Otherwise these wild animals are treated as such and are left alone unless one is seen to be in distress.

On the Sunday before the talk, Matt had to rescue one of this year’s pups exhausted in the mud just next to Orford Quay.. They took the pup in for observation, coordinated with partners from the British Divers Marine Life Rescue and the RSPCA, and with one of the volunteers from BDMLR, the decision was made that it had recovered and was a good weight, so it was returned to the Ness and safely released.

Summation:

Matt would never have expected that seal management would be part of his job specification but is supported by having access to so many experts and such a breadth of experience within the organisation – such as curators, archaeologists and ecologists. The National Trust is a huge organisation with such resources but there’s still so much to do. Matt is proud to work for it – and it’s also great fun.

Some questions:

- Matt was asked about the amount of bracken at Dunwich. He replied that it’s coming through much more strongly than the heather as it’s faster growing and the drought damage means less competition from the slower-growing heather. This means they must go ‘bracken-bashing’ which has always been part of the annual program for work. NT prefers physical management rather than herbicide spray.

- He was asked about Northey Island. He replied that they are predicted to lose the majority of it in 100 years. However the recent realignment work that has been carried out has extended the life of the remaining productive land by approximately 40-50 years.

- He was asked about the Orford Ness seals eating the fish stock. He replied that the seals simply wouldn’t be there if there were no ood sources. Despite appearances, they are also not there all the time; when they’re not pupping or moulting, they’re out feeding and foraging well out into the North Sea.. The Sea Mammal Research Unit at University of Saint Andrews have GPS tagging data as to where the ‘Ness’ seals go. They travel significant distances in a given year, crossing the Channel several times and also visiting Lincolnshire, Yorkshire and the Farnes.

- He was asked about unexploded ordnance at Orford Ness. He replied that there hasn’t been any identified for a while, but it is always a consideration and expected that something will turn up! The MOD “surface cleared” the site over a number of years when NT took it over and removed 250,000 pieces of ordnance at the time, but it is estimated there are probably half a million pieces still there. The dynamic and moving nature of the shingle means that things will work up to the surface – like the larger lumps in a muesli box. When that happens there are processes in place to ensure safety and call Bomb disposal.

- He was asked about equal access. How do they stop people damaging sites? He replied that for most people, education and engagement works really well. For example, there has traditionally been public access at the southern end of Orford Ness for recreational camping, bonfires and dog walking. However the NT are trying to protect the Lesser Black-Backed gulls whose numbers have dropped by over 90%. They have introduced crossing paths and signage to avoid the nesting sites, as well as routine patrols by staff. Now, just a couple of years into the project, we are seeing local users are redirecting others. Their approach is soft engagement but it must be sustained so that people don’t lose sight of the message. Concerning Northey Island they have events during ‘open’ season and work with other partners in the stuary – which shows the value of the island being closed for the winter months due to its wildlife significance.

The RDA is most grateful to Matt Wilson for this extremely interesting and informative presentation with excellent slides.

Artist Jeremy Young was also at the AGM giving RDA members the opportunity to be the first people to see his newly published limited-edition book of photographs exploring the ancient woodland at Staverton Thicks. Members were also asked to give feedback on a preliminary selection of forty photographs (from approximately 1500!) These represent the early stages of One River – a limited edition book that will illustrate aspects of the tidal Deben from Wilford Bridge to the bar buoy.