Matt Lis

If a mast breaks in a marina, and nobody is there to hear it, did it really happen? Well, sadly, yes and it won’t take long for everybody to hear about it.

In my case, it took about 10 minutes to hear about it when, late on a Sunday evening, the work mobile rang and I answered to find Julia close to tears. A misjudged approach into a marina berth in semi-darkness had led to ‘Peter Duck’s portside mizzen shroud catching on the cranse iron of a neighbouring boat. For those less familiar with the particular peculiarities of traditional boat rigging, the cranse iron is the fitting on the end of a bowsprit on to which the bobstay, forestay and bowsprit shrouds attach and it is designed to handle immense loads so it had no trouble winning this particular battle.

With a sickening splintering, ‘PD’s 70-year-old hollow mizzen spar had broken close to its gooseneck fitting, the swivelling fitting which connects the boom to the mast.

I hopped in the van and soon we had the mizzen safely on deck with its wiring disconnected and the problems could wait for the insurance office to open the next day.

Having received approval from ‘Peter Duck’s insurers, timber was ordered. ‘PD’s masts are both made of Sitka Spruce, a fantastic timber for spar making due to its terrific strength and light weight. Spar-grade spruce comes from Canada and is increasing hard to buy in long, high-quality lengths suited to mast making but through a close relationship with specialist importers we are still able to source what we need.

There are many ways to make a wooden mast with many pros and cons. The simplest are a solid, round poles like a telegraph pole (some of them actually are repurposed telegraph poles), some are made in two halves and some are made of many staves of timber that are glued together.

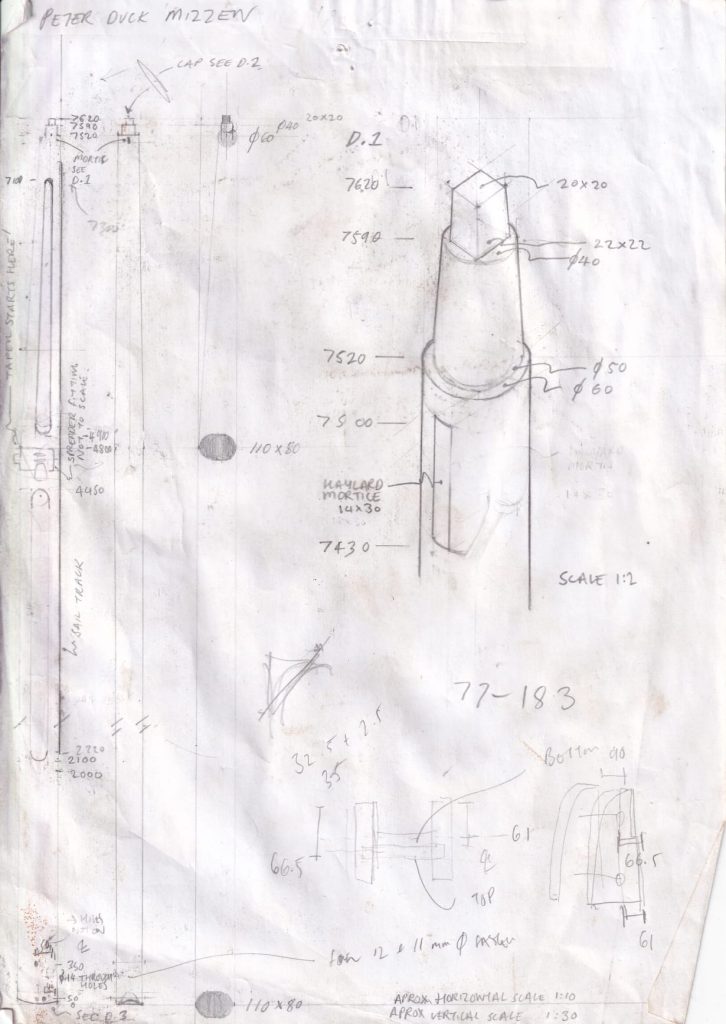

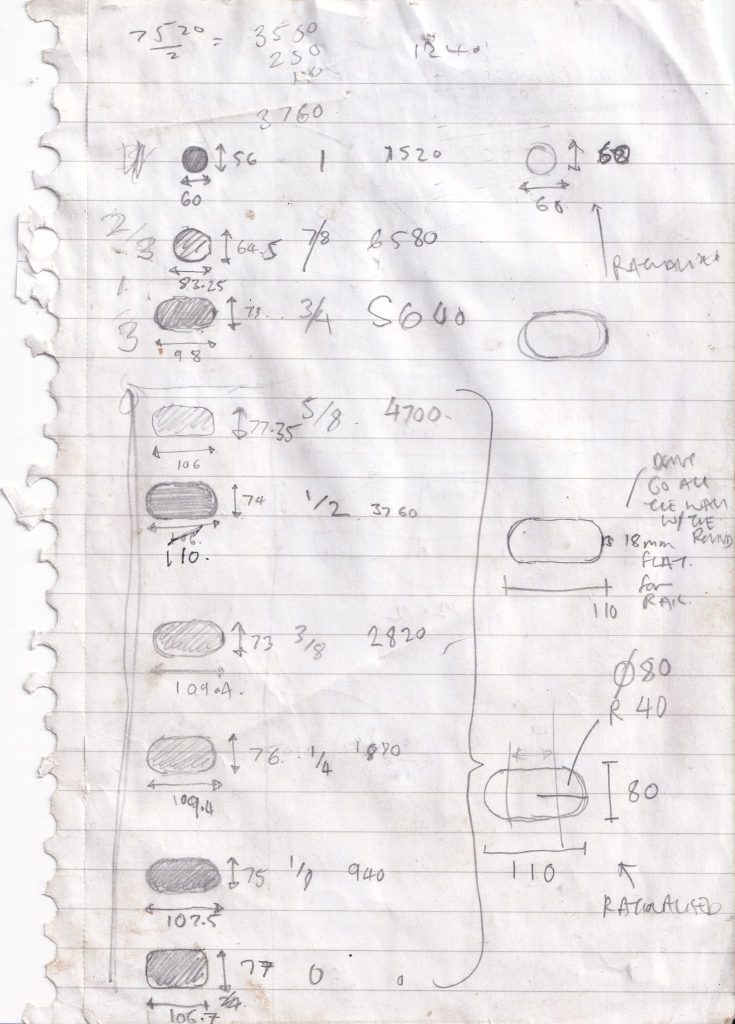

‘PD’s mizzen mast is made in two halves with a hollow centre to reduce weight. Through its 7.62m length it transitions from a near rectangular base to a lozenge shape for much of its length, tapering in its top half and transitioning to a round section. The tapering and transitioning shape must all be achieved without interrupting the shape of the luff (the forward edge of the sail) or reducing the internal wall thickness in an uneven way which will affect the way in which the mast (intentionally) bends or creating weaknesses.

In this case it was Jem from our team of shipwrights at Woodbridge and Waldringfield Boatyards who took on the task in hand.

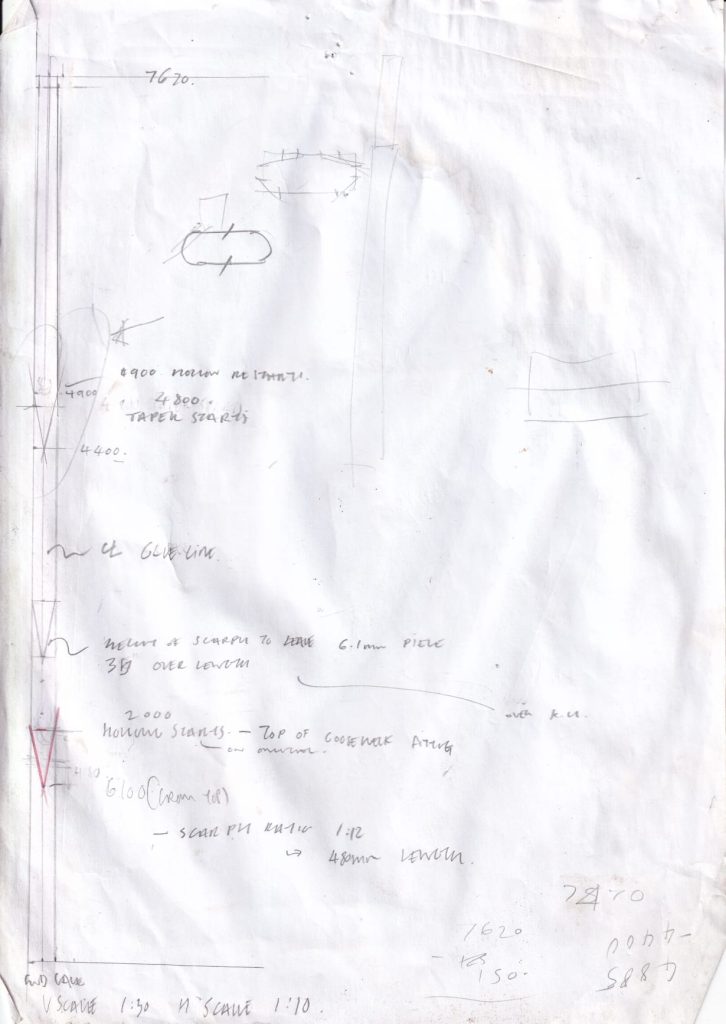

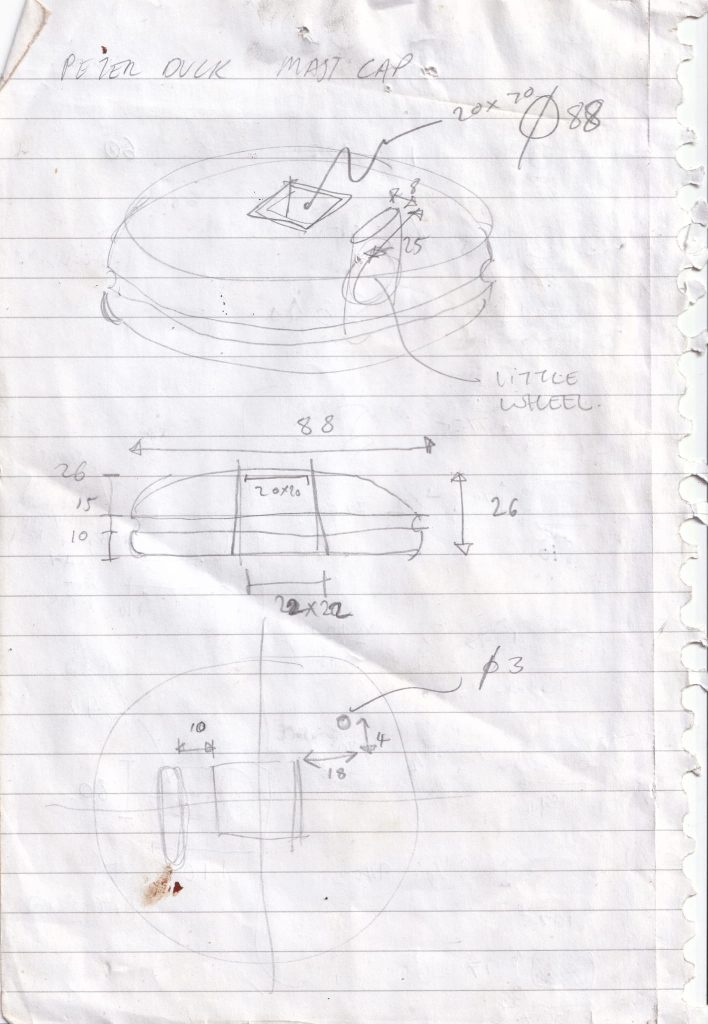

The first task was to survey the broken mast, plotting out the changing shape and the location of any hardware or other critical information. As well as taking lots of photos, Jem made a series of technical sketches to capture the detail and plan the construction of the new spar.

With a plan in place, the timber was selected, sawn and thicknessed to its starting dimensions. The timber available to us was not long enough to make the mast without joining it, however it was wide enough that we were able to rip and resaw a single piece of wood into the four pieces that we required.

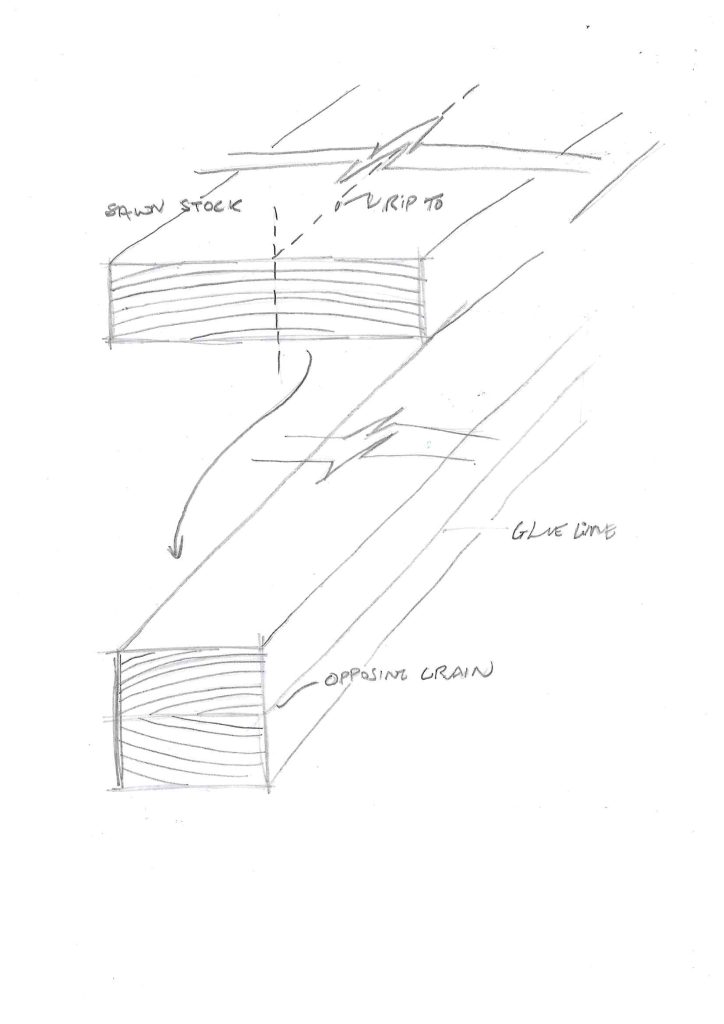

To counter the natural inclination that a piece of wood may have to bend over time, it is good and normal practice when making a two-piece mast to turn the wood of one side of the mast ‘upside-down’ so that the grains of the pieces oppose each other and should they want to bend, they should counter each other cancelling the effect out.

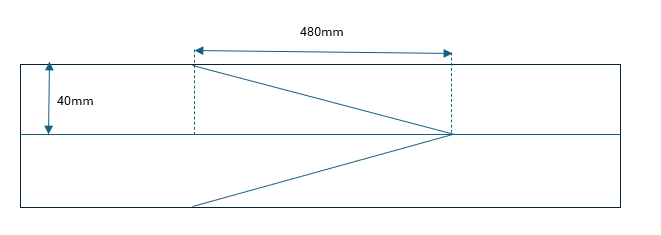

‘PD’s mizzen mast is hollow along most of its length so the scarph joints which would join the wood together to make it longer, were positioned to happen in the only section of the mast which is not hollow, the point 4.5m up where the spreaders are mounted to the mast. With this decided and the timber ready, it was time to hollow out the centre of the mast. The original mast was likely hollowed out with chisels but now the mechanical muscle of a router can make lighter work of the same job. Modern glues also allow us to paint out these cavities with epoxy to protect them from any water that may find its way inside. At this point the scarphs were cut. For a mast, a 12:1 ratio scarph is optimal so, since the mast at that point is 80mm thick but that thickness is made up of two pieces of wood glued together, each of these scarphs is 40mm thick and therefore 480mm long. A pair of scarphs arranged in this fashion are referred to as a bird’s beak scarph, potentially confusing as ‘bird’s mouth’ is also the name given to another method of mast construction.

Now at its full length but in two halves, the mast is ready to be glued together. For masts, we prefer to use a resorcinol-based glue. Resorcinol glue dates back to WWII and was revolutionary for the making of timber-framed aircraft like the Mosquito. It requires pressure to get good adhesion with resorcinol so it is essential to have lots of cramps (or clamps if you prefer) ready and to ensure that the glue is squeezing out evenly along the length of the workpiece.

We now have our basic mast to its correct key dimensions, but it is square or rectangular in this case. The next step is to turn our 4-sided rectangle into an uneven 8-sided octagon and then into a 16-sided (Do you know what it’s called…?) hexadecagon.

At the same time, whilst achieving more faces, the taper is created. In the case of ‘PD’s mizzen, that taper begins immediately above the spreaders (and our scarph joint) and the mast must simultaneously reduce in size whilst smoothly transitioning from a lozenge shape measuring 80mm x 110mm to a round section of 60mm x 60mm; a test of the boatbuilder’s maths as well as their skill to smoothly lose exactly that 20mm (about 3/4 of an inch) over 2.8m (a little over 9 feet). To add a further complication, the mast tapers evenly in its width, losing 10mm from either side, but the taper from 110mm to 60mm happens all on the leading edge of the mast, with the trailing edge remaining straight.

With ‘Peter Duck’s masts, the transitions happen over long distances but in the case of round masts which may fit into square tabernacles or flag poles (such as the war memorial flag poles in Woodbridge which were also made at Woodbridge Boatyard), the transitions from square to round sometimes have to happen very quickly.

Once we have 16 sides and our tapers where we want them, we are ready to start sanding to reach the final fair curves of a round, teardrop or lozenge-shaped spar. Some of this sanding can be mechanised but, generally, it has to be done by hand to avoid putting any flat spots into the curved surfaces.

With the mast sanded fair and down to 240 grit, it is ready to go through to the paint shop. ‘Peter Duck’ has varnished spars and we built the new mast up to 10 coats using an Epifanes system flexible enough to move with the mast and offer it years of protection.

Finishing touches now, as Jem dressed the mast with its hardware and rigging. Thankfully since it was replaced only 3 years ago, only the one shroud was damaged and a new one could be made to its pattern. All finished, the mast was stepped and ‘PD’ looked like herself again, a handsome Bermudian ketch once more and with a mizzen that will last her many decades (if kept a safe distance from malevolent bowsprits).

Matt Lis

Matt Lis is General Manager of Woodbridge and Waldringfield Boatyards. He grew up in Burnham-on-Crouch, Essex, studied Marine Engineering, and worked for a marine engine manufacturer and an electric vehicle start-up before moving to Woodbridge in 2019.

Woodbridge Boatyard was founded in 1889 as Everson’s and continues to be a strong local boatyard with a particular focus on wooden boat repairs.

Waldringfield Boatyard was founded in 1921 by the Nunn Brothers, former apprentices of Everson’s.