By Robert Simper

Most people seem to get into writing from journalism or being connected with a university. I started writing because an incident unloading a lorry. Back in the 1950s, drivers unloaded their own lorries. I took a load of oats in bags into the ECF (Essex County Farmers) mill in Commercial Road, Ipswich and cheerfully grabbed the last bag of the load and swung it round. At the same time something awful happened in my lower back. I spent the next ten years getting over it and have had to be careful ever since.

It was Dr Ian Simpson at Alderton who said I should stop going the surgery about my back problems and get another occupation which didn’t involve heavy lifting. I had always read a lot and thought, half to kill time while resting with back pains, perhaps I could write something. Writing, after all, involves nothing heavier that lifting a small typewriter.

Like most aspiring writers I assumed I must be an undiscovered genius. So it came as a surprise that nobody was in the slightest bit interest in any thing I wrote. However, I picked up that you were supposed to have a ‘style’. Eventually I just wrote as I spoke and that seem to work.

I was writing in the evenings, longhand with a pen, but my wife Pearl said if I was serious about this, she would go to evening typing classes. We had a portable Olivetti typewriting and for next twenty-six years Pearl typed out all my material on it.

My friend Ian Clarke said he used to meet Ronnie Blythe in the Bell and Steelyard and he was a ‘Writer.’ Ian fixed up a meeting with Ronnie who then lived in a house outside Charsfield and was just finishing writing his bestselling book Akenfield. Ronnie wanted to put me in this book as a young man from rural Suffolk. I thought this might be good information that I should keep it to myself, as it might be material I could use later, However Ronnie was keen to chat away about the art of writing, which he understood. I remember him saying that when you write, you should ‘step outside yourself’ and express emotions you would not normally talk about. Also be honest because readers will soon spot it if you are lying.

One day, something I had written appeared on deck of James Wentworth Day, then editor of the East Anglian Magazine. He wrote to me saying my spelling was awful and the grammar was even worse, but clearly, I knew how to put a story together and must go on writing. James ended by commissioning me to write a series of articles for his magazine. All this was picked up by ‘Rim’ Booth at the East Anglian Daily Times. and he asked me to write for their agricultural pages. I started doing a bit of journalism, rushing to telephone boxes and phoning in copy about events. All of which gave Booth more time to stay in Ipswich pubs.

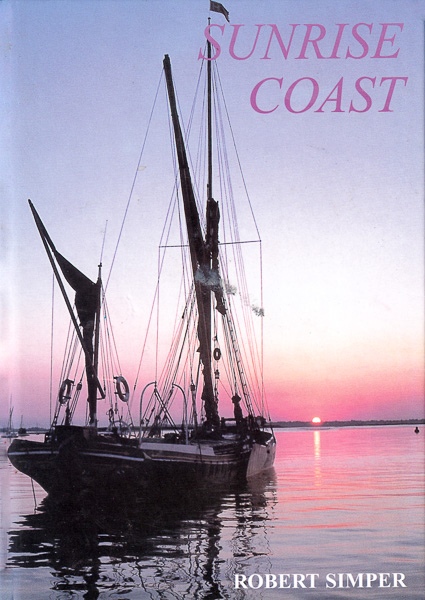

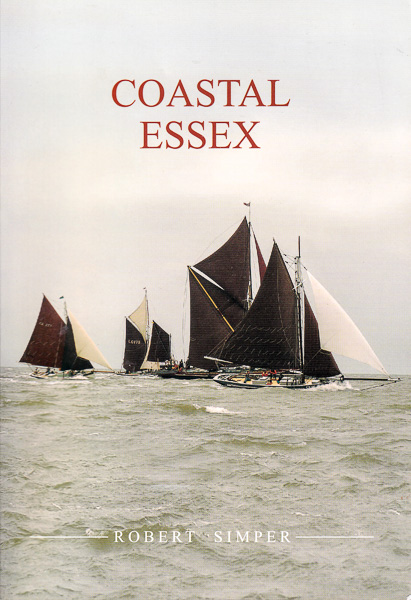

Soon small cheques started to arrive, which with three children came handy for something I did after tea. However, writing about agriculture was too much like my day job, so I switched to writing about my interests in traditional sailing vessels. In 1966 the magazine Sea Breezes asked me to write their ‘Sail Review’ features and, fifty-five years later, I am still writing it, having travelled all over the world looking for traditional work boats.

I could see the EADT was never going to be a high payer, so I started doing pieces for yachting magazines. Soon editors said, ‘OK, the words are fine, but where are the pics?’ I certainly couldn’t afford to hire photographers so I went into Ipswich and bought a camera, About this time, at a party in Hemley I meet Michael and Pam Boys. Michael was successful London Photographer and was intrigued with me. He said, ‘How did you in a Suffolk village just sit down and started writing and get stuff published, some people try for years to do that!’

Michael gave me a crash course in photography, but the most valuable long term help came from Pam, who ran the office side of their business. She said, ‘You must make a detailed file of every role of film you shoot, because you can often can sell them years later, we do.’

I sort of got the hang of photography but was fairly hopeless at filing. However I did keep a lot of records that have come in useful, though nobody wants black and white photographs now. I found I could look though the features and photographs in a publication and work out what the editor was likely to accept. Unfortunately other people were doing the same thing and sometimes a weary letter came back saying they already had got a pile of articles on the subject. Sometimes it did lead to editors commissioning a piece.

That is how I got into writing travel articles for the London papers. These were mostly just one-off pieces, but I did contribute travel features to The Sunday Telegraph’ for a while. Editors began pushing travel trips (that they didn’t want) my way. There were a lot of day trips but it also sent me on a passenger schooner to the Windward Islands in the West Indies. I was only foreigner amongst about hundred Americans. They were lovely people and wanted me to join in, but somehow I felt very alone. Next time I asked if could take ‘my photographer’ and I think they guessed this was going to turn out to be my wife. So Pearl came with me to the Windward and Leeward islands, Panama Republic and a trip on five-masted square-rigger around the Italian coast. Some payback to her for all those hours on a portable typewriter.

With magazines, if your material was not what they wanted they simply didn’t take it, but with publishers the key to success was working with their editors. A publisher’s editor helps shape the finished work. However for this to work well, the author and editor had to have the same aims. Sometimes, when the editor became too involved, the whole project got confused and failed.

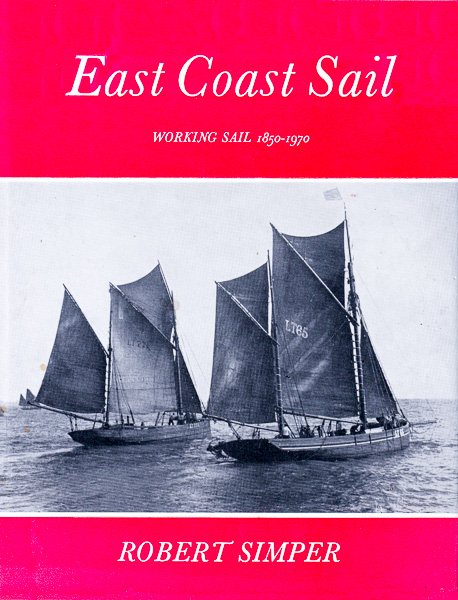

I had actually written my first little book, Over Snape Bridge back in 1967, but found the publishing world was totally closed to me as I had no literary background. My first real breakthrough was East Coast Sail in 1972. This sold well and the publishers, David & Charles in Devon, wondered if had any other ideas.

I did five books, mostly about the coast around the British Isles, for David & Charles. I got on really well with their editor, James MacGibbon, who said a book belonged to the author and the publisher should just help them to achieve their goal. James was a sailing man, who had had his own publishing business and I think he was filling in time before he retired. He was very happy to tell me the background to the publishing world. Basically, publishing is informed guess work, no one really knew what would sell until it hit the bookshops.

David Thomas, part owner and driving force at D & C, didn’t seem to like James and I guessed he was a bit of rebel at heart. I was really surprised, after James died, that his family revealed he had spied for the Soviet Union during World War II. He had been in Intelligence and realized the Allies were not passing some information to Russians. James had filled the gap by leaving notes in a London park for other spies to pick up. In the 1930s James must have become a communist, but this had not been picked up. After the family revelation, however, some London newspapers claimed that British Intelligence had used him to pass on ‘fake news.’ In that world who knows what really went on?

David & Charles published my best selling book, Britain’s Maritime History in 1982. I still get small payments for it being taken out of libraries. D & C had said I had a year to write the book, which I was doing in evening, and Pearl typed it out the next day. Suddenly I was called by their London base and was told that a rival publisher had come up with same idea and I now had nine months to finish the book.

Both Pearl and I had to work long hours to meet the deadline but there was financial reward. The well-worn Olivetti went into cupboard and we proudly bought a word processor. However, we never wore the word processor out because computers were coming in. In 1987 it joined the Olivetti in the cupboard.

I always found that publishers and most magazine editors were very honest, but when I tried to get material used on television, I found them totally unscrupulous. Producers would happily ask me to write outlines for programmes, then say it was not suitable, but actually pass it to their own writers to use. I am fairly certain over a period of about two years I spotted at least three of my ideas appearing on the small screen. One I did on sea defences appear almost word for word, but they put a better ending on it.

Perhaps the way forward was to make a programme and sell it to television company. I joined forces with Graham and Honour Hussey of Butley. We got a good cameraman and Honour did the directing. We were trying to fill a half and hour slot, but finished up with programme only twenty-five minutes long. The BBC clearly like it, but they found it easier to simply buy one the proper length. With television you have to come up with right goods.

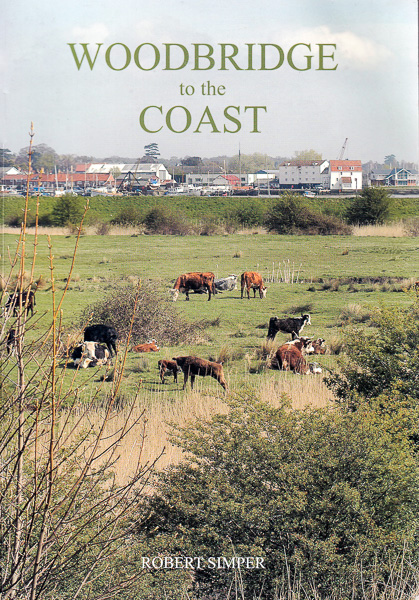

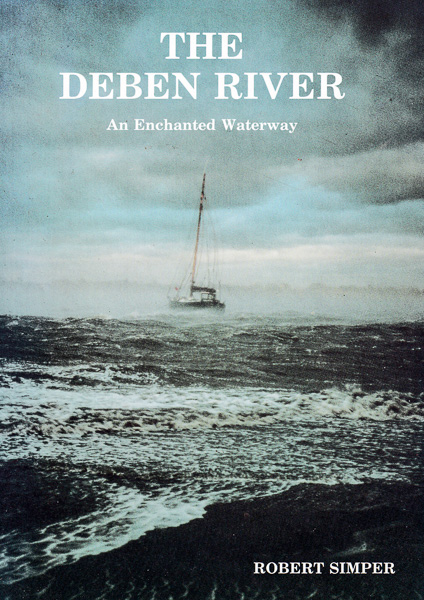

I was tiring of writing books and articles on subjects which other people had thought of but I got into publishing almost by mistake. Graham Henderson of Felixstowe Ferry asked me to help him write a book about the River Deben. It was not long before I worked out Graham wonted me to write the book and he would be the salesman – which he was good at. I wrote The Deben River in 1992 and Graham lent a few Felixstowe Ferry photographs. I was used to running a business, so I organized Lavenham Press to print the book and began a long relationship with them.

Graham said he wanted to take all the profit from selling the book so he would hire a hall and sell the whole lot in one day. My approach was to sell through book shops thus giving a long period of sales. We didn’t fall out, but split the print run in half. I assume Graham had a profit day selling them. I reprinted this book twice more, and years later I bought Graham’s remaining copies from him and sold them around the shops. At Graham funeral it was said he had written The Deben River but Robert Simper had helped a bit!

I could see that the format of The Deben River was a winner and I thought I could go on the same with other East Coast rivers, starting with The River Orwell and the River Stour. This became a series called the English Estuaries and Pearl and I now became Creekside Publishing because that was what we were doing beside the River Deben. I wrote eight in this series. but by the time we got to writing Rivers to the Fens in 2000 it was rather a long way from home and we were spending an awful lot of time travelling. It also true that the further away from home I got the less I felt attracted to the rivers. I really wanted to write about my home river and its neighbours, about which I felt strongly.

I seem to break all publishing rules. You should have a print run which sells fairly quickly. Obviously this is good for cash flow and often publishers don’t have enough storage space. I had barns so storage was not a problem. I printed too many, but saw no point in going around to shops just selling one or two titles. The books are supposed to be written in timeless way so that they would go on selling for years – which they still do.

I have always relied heavily on good illusions. There is a old saying ‘a good picture is worth a thousand words’ and it is true. We employed artists to draw maps and illustrations and usually by the time we came to next book, the artist was on some other project. However I realised that by having different artists, each book looked more original.

Pearl did the accounts and began to find this a strain. We started to pull back the business. We were both in our late seventies so I said Beachman’s Coast; Suffolk in 2015 would be my last book. However, Martin Whittaker on Browsers Books, Woodbridge had long wanted me to reprint Woodbridge & Beyond which had already been reprinted several times since it was originally published in 1972. I wanted to do a better version and the discussion went on for years.

In the end it turned out that one of the editors of the publishers Boydell & Brewer lived above Martin’s bookshop and this led on to them agreeing to do a up to date version of my Woodbridge book under the title of Woodbridge: A Personal History. This was published by their new imprint Three Crowns Press. Boydell & Brewer are very successful academic publishers. They had published two of my books in the 1980s when Richard and Helen Barker had run the business from offices behind Stangrove Hall in Alderton . It was really good to see how the firm had grown, though my chatty way of putting across history was totally different to other books on their lists.

In the end it turned out that one of the editors of the publishers Boydell & Brewer lived above Martin’s bookshop and this led on to them agreeing to do a up to date version of my Woodbridge book under the title of Woodbridge: A Personal History. This was published by their new imprint Three Crowns Press. Boydell & Brewer are very successful academic publishers. They had published two of my books in the 1980s when Richard and Helen Barker had run the business from offices behind Stangrove Hall in Alderton . It was really good to see how the firm had grown, though my chatty way of putting across history was totally different to other books on their lists.

Then I got a suggestion that my original Over Snape Bridge could be up-dated with a new title Over Snape Bridge Revisited. That might have been the end, but along came covid-19 and we all went into lockdown and I sat at home looking for something to do…

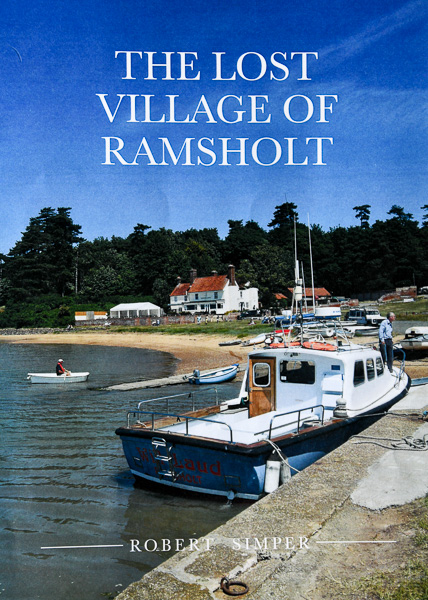

When Pearl and I got married in 1959 and moved to Ramsholt I had started to collect the history of the village with aim of one day to put it all down on paper. Ramsholt is a strange empty place to live in, and over the centuries very few records about it have survived. It took decades to work out what probably went on. I have been trying to trace the village’s history most of my life and have still not filled in some of the blank. I thought I would publish what I had and that might help future researchers. The Lost Village of Ramsholt (book number forty-two) came out in the pandemic, which might have been worst possible time, but people wanted something to sit at home and read so nearly all the boxes were sold very quickly.

Once, years ago, some critic of my printed words said, ‘ You can write that stuff about sailing boats in your sleep; real writers can write about any thing!’ I thought this was good point so I had a period writing about anything. I once wrote a piece about climbing the Matterhorn, researched on a winter Saturday afternoon in Ipswich Library. I have always hoped nobody got injured or worse after reading this.

Robert Simper

Robert Simper has lived on the Deben all this life. He was a founding member of the RDA and is now its president. His most recent title ‘The Lost Village of Ramsholt’ was published in October 2020 and reviewed in The Deben #62. It was also the subject of an RDA article ‘Two Sides of a River’ by Julia Jones (9.1.2021).

.