By Gareth Thomas

From HOO to MELTON and BROMESWELL

It is best to read Part 1 before venturing further down river and, in particular, to refer to the time-line table.

Now I am neither a good photographer nor a professional historian, nor a geographer, cartologist or ecclesiast so there are very likely to be imperfections in my observations on the Churches of the Deben – massive imperfections, quite possibly. However, I am very happy to be corrected for that is a good way to learn.

Talking of learning, in 1963 I became a medical student at St Mary’s Hospital, London. Those were the ancient of days when medical training was based very firmly on an intricate knowledge of physiology and anatomy. I felt obliged on arrival to buy a half-skeleton to help with the learning of anatomy. It came from either South America or India via Adam Rouilly and Sons; it was real, male and in a wooden box. The skeletons are made of plastic these days, but true anatomists will tell you ‘they are not the same’.

You may be wondering what on earth this has to do with Churches of the Deben, but you will know from Part 1 of this series that I am not averse to wandering ‘off-piste’ at times. My half-skeleton stayed with me until this last year, 2023, but it now resides in the Department of Anatomy in Cambridge University. Whilst with me he became known in the family as Huwie (short, and Welsh, of course, for ‘who is he?’) or, in English, Hooie. As a consequence, I cannot help being reminded of ‘him’ whenever I think of Hoo and its church. No headstone, wall plaque or ledger-slab for my Huwie but at least a quiet moment to acknowledge with thanks the unknown person who helped me, and others, to learn our anatomy. There is no better place than Hoo in Suffolk in which to have that quiet moment.

The Church of St Andrew and St Eustachius at Hoo. The tower peering mysteriously through the bare branches

The Church of St Andrew and St Eustachius at Hoo. The tower peering mysteriously through the bare branches

– – –

The Church of St Andrew and St Eustachius in Hoo is situated just under 400 yards to the south of a sizeable southern loop of the River Deben and immediately adjacent to Hoo Hall, a 17th century farmhouse which, according to the Suffolk Heritage Explorer website, is assumed to occupy the site of a medieval manor.

The ambience around this church is truly Suffolk – there is nothing in the immediate vicinity except the Church, the Hall, the old Rectory, a working farm and horses grazing, dressed from head to tail to protect them from the cold. The lanes leading to the church are single- track and lined by spaced oaks, now without their leaves but, nevertheless, standing proud. Looked at from the north-east the church tower peers mysteriously through the bare branches of the trees whilst, to the south the light stone and flint walls of the nave and chancel reflect the warmth of the sun and invite you to explore inside. Such is the ambience that the church was used in Sir Peter Hall’s 1974 film ‘Akenfield’, based on the book of much the same name by Ronald Blythe – ‘Akenfield: Portrait of an English Village’. The book was mainly about the village of Charsfield, a few miles to the south, but the churchyard there was too small for all the filming gear so the open space around the Church of St Andrew and St. Eustachius was put to good advantage.

The Church of St Andrew and St Eustachius; southern aspect. The greenhouse directly ahead made me think, at first, that I was back in France where tombs are often protected in that way! However, it is a genuine horticultural greenhouse in a neighbouring garden.

– – –

The mid-Loes Benefice website tells us that a church has stood here since before the 1086 Doomsday Survey; in Saxon times the Manor of Hoo was held by the Abbot of Ely. The nave and chancel of the current building date from the 13th and 14th centuries as evidenced by the “Y” traceried windows in the south and east wall.

Like the Suffolk countryside which surrounds it, Hoo Church is uncomplicated, both outside and in. The sixteenth-century, Tudor-brick tower is magnificent both in its simplicity and its architectural elegance (although the top is a more recent addition which spoils it just a little) The roof-line of the church is unstepped and inside, there is no division between nave and chancel. However, the position of the rood stairs in the south wall and the absence, through levelling, of the chancel steps, indicate that there probably was a division when the church was first built.

The Church of St Andrew and St Eustachius, showing especially the elegance of the 16th century brick tower

– – –

Inside there is no pretension; the cross beams, the pews and the pulpit are simple and functional. One of the beams carries a date – 1595 – but that may have been the date when the old timbers were boxed. The rood stairs ascend from a window alcove and can only be seen when looking toward the nave from the chancel. At the back of the nave, against the north wall, there is a 14th century chest with a complicated looking locking mechanism; it makes one wonder what treasures may have been stored within – parish registers in times past, no doubt.

There is an early East Anglian font, badly defaced, probably on the orders of the Puritan Will Dowsing who was also responsible for the levelling of the chancel steps, circa 1644. William

Dowsing, Suffolk born, was a jobsworth appointed by the Earl of Manchester as “Commissioner for the destruction of monuments of idolatry and superstition” as per a Parliamentary Ordinance issued in 1643.

Inside St Andrew and St Eustachius there is no pretension

The rood stairs, looking west from the chancel

The 14th century chest and its locking mechanism

– – –

Specifically, the objects to be destroyed were “fixed altars, altar rails, chancel steps, crucifixes, crosses, images and pictures of any one of the persons of the Trinity and of the Virgin Mary, and pictures of saints or superstitious inscriptions.” In May 1644 the list was made even longer by the addition of “representations of angels, rood lofts, holy water stoups and images in stone, wood and glass and on plate.” Smasher Dowsing (so called because he often did the damage himself) was reputed to be particularly anti-angel and averse to raised chancel floors. He kept a Journal, Dowsing’s Journal, of his activities in Suffolk and Cambridgeshire.

The font, damaged either by, or on the orders of Will Dowsing. This poor angel is without its face and has lost most of its left wing.

– – –

It is time now to leave Hoo and head for Kettleburgh. The Church of St Andrew in Kettleburgh is just visible from Hoo, to the north-east, through the trees; there is a Scottish flag, a saltire, atop. According to the map it is about 750 yards away but there is a river between us and it, and, also, quite a wide river valley, as we will see shortly.

From Hoo, the river completes its southerly loop by swinging north beneath Dowsing’s bridge before heading in an easterly direction for Kettleburgh. One can almost feel Dowsing stomping over that footbridge, heading with mal intent from Brandeston to Hoo.

A glimpse from Hoo of the Church of St Andrew at Kettleburgh. It proved ironic to see it from there bearing in mind the difficulty I had eventually finding it!

– – –

The Church of St Andrew at Kettleburgh is situated nearly 650 yards from the river and for that reason I was sorely tempted not to include it. Nevertheless, the people who built, used, cared for, damaged, rebuilt and renovated this church are very much the people who used and experienced the local river, and, probably, the local pub, the Chequers which is less than 50 yards from the river – in fact, its garden lodges look directly over the river. So, despite the distance, attributable to the ‘drawn-out’ nature of the old village, St Andrew’s gets included. Besides, to be entirely fickle, in a frantic search to find connections between the Deben churches and smuggling, the only name which has cropped up so far is Kettleburgh and even then, there was no mention of St Andrew’s or it’s even more distant and remote old rectory!

That said, it is an article entitled ‘Past Times’ in a Brandeston and Kettleburgh church magazine which alerts the reader to the existence of the infamous Hadleigh Gang, a group of up to 100 men who would bring contraband from the coast at Sizewell Gap to the village of Semer, near Hadleigh, a distance of about 40 miles. It seems from other accounts of smuggling that each member of the gang would have two horses and that most of the contraband would be carried by wagon or cart. They tended to use the old Roman road from Peasenhall to Coddenham because the condition of alternative routes was so terrible – nothing changes! Nevertheless, according to the magazine article an ‘incident took place on a May Sunday afternoon of 1874. The Hadleigh gang had moved 57 casks of brandy and rum from the coast as far as Kettleburgh where a dozen (revenue) men lay in wait. The officers captured the contraband and began their journey to Woodbridge’. However, a ‘bloody engagement’ took place near Easton as the smugglers attempted to regain their ‘stolen’ goods. The revenue men won and many of the smugglers were seriously injured.

One has to ask why the smugglers were passing through Kettleburgh, because the Roman road certainly does not. Perhaps it was a good place to cross the Deben, perhaps there were good places to hide, perhaps they were bound for Monewden where, in the previous century, the sexton had been heavily involved in smuggling, hiding contraband behind an oak panel depicting the ten commandments!

Approaching Kettleburgh and its bridge from the west there is an increasing awareness of low-lying woodland on either side of the road, and the appearance of raised wooden walk-boards suggests that the road might spend a significant time below the flood waters of the Deben.

Approaching the river bridge at Kettleburgh. The trees on each side are rooted in mud.

The bridge over the Deben at Kettleburgh

The raised walk-boards just before the bridge – suggesting that flooding is frequent

Up-river at the bridge – there used to be a mill up there

– – –

I am just trying to build up the picture that the Deben valley is a lot wider than the river and that, at some stage in the last 2000 years there was a lot more water in the valley, whether concentrated in one river or flowing in several parallel courses can only be guessed at.

In every account one reads of St Andrew’s Church, there is reference to its ‘remoteness’ – Arthur Mee wrote in The King’s England – Suffolk in 1949 that it was ‘hidden away from the village’. That is not now the case as modern housing connects the old village and the Church. In days of yore both the Church and the Rectory were well apart from the rest of the village and they themselves were separated by the best part of 500 yards. The Ordnance Survey map shows an antiquarian moat between the two which might suggest that the Church and its predecessor building were part of a medieval settlement and that the village developed separately nearer the river, perhaps because of a mill. Of course, one must always remember the influence of the Black Death and the plague on the development of the average English village. Often, settlements immediately adjacent to churches were wiped out by pandemics, never to be replaced.

Anyway, that is enough theorising. St Andrew’s at Kettleburgh is at the northern extreme of the village and is easily missed. The difficulties were compounded by road-blocks at the entrance to Church Lane but I got there in the end. Church Lane itself appears to peter out with a notice to drivers stating Access Only. I parked and walked and suddenly there it was – the Scottish flag – the flag of St Andrew (you will have to take my word for it – but see the next photo by which time the wind had got up!) flying from the tower of a very attractive looking church.

The Church of St. Andrew, Kettleburgh – but how to get to it? That looks like a pretty stout hedge to me.

– – –

The church appeared to be on the other side of a pretty stout hedge with no obvious gap or pathway through, so I ventured further past a great big wooden gate into what appeared to be someone’s front garden. The ‘someone’ was very helpful; he explained that the gate was a delivery-van-turning deterrent, that the church was open and that I was welcome to pass between his cottage and the cottage next door in order to reach the churchyard. These two cottages are the only buildings of antiquity anywhere near the church.

There was a place of worship on this site in 1086 but the existing church was built mainly in the 14th century. The tower was completed in the 15th century. The pulpit and the font cover are Jacobean (early 17th century when carved oak was ‘in’). A great deal of modification took place in 1891 including the removal of a gallery, the installation of the rood screen and the reduction of pulpit from three tier. A modern wooden floor at the west end of the nave contrasts with what the church guide describes as the ‘ancient’ south door. The pews in the nave came from St. Mary the Quay in Ipswich just after World War 2.

An historian friend of mine once reminded me never to forget to look up when examining architectural treasures. One of the church guides I have read recently, I forget which, advises that one should lie down in a pew in order to ensure a good examination of the roof. The risk is that someone else might enter the church during the period of recumbency, consider one an itinerant of no fixed abode and flee in terror. Semi-recumbency is the answer – rather like Rees-Mogg in the Commons. It is, however, easier to obtain complete symmetry, and so better photographs, with complete recumbency

On entering the Kettleburgh churchyard the eye is drawn to the large celestory (upper) windows which give the building a rather homely look. Either they are there for extra light in the nave or there were plans for a south aisle and removal of the lower windows. Like Hoo, the tower is elegant in its design but built, not of brick, rather of stone and flint.

– – –

The lock in the ‘ancient’ south door at Kettleburgh

– – –

Semi-recumbency in St Andrews led to two observations on my part. First the simple repeated panelling just below the roofline, at the top of the north and south walls of the nave. Presumably oak, and without colour, the carving of each panel resembles the saltire which is particularly appropriate for a church dedicated to St Andrew. The second observation was the presence of ten brightly coloured shields, five on each side.

These shields were gifted and dedicated as recently as 1999 and according to a pamphlet prepared by the Rev.R.J.Dixon and available in the church, they represent ‘some of the history’ of Kettleburgh. Included are shields showing the three coronets of East Anglia, the three mitres of the Diocese of Norwich (which was first centred on Dunwich or Walton), the three coronets with demi-lion and demi-ship of the Diocese of St. Edmundsbury and Ipswich, the shields of local families, the Pennings, the Stebbings and the Charles, and the three lions of King Henry III.

Looking from the nave to the chancel in Kettleburgh. Note the finely carved rood screen and, to the right, rood steps ascending from the lowermost part of a window recess (which is also the top of an occupied coffin built into the wall) To the left, close to the pulpit there is a closed archway, which, when it was open, led into a chantry chapel of the Charles family.

Looking from the nave to the chancel in Kettleburgh. Note the finely carved rood screen and, to the right, rood steps ascending from the lowermost part of a window recess (which is also the top of an occupied coffin built into the wall) To the left, close to the pulpit there is a closed archway, which, when it was open, led into a chantry chapel of the Charles family.

– – –

A section of the roof timbers at the Church of St. Andrew in Kettleburgh, slightly over-exposed to show the oak panels with crosses resembling the saltire flying from the tower in an earlier photograph. Also in the picture – the shields of East Anglia to the left and the shield of the Penning family to right.

– – –

I particularly liked the final paragraph of the pamphlet, part of which reads as follows:

“This selection of shields thus represents the whole range of the land-holders in the feudal system of the Middle Ages: landed country families, great Lords, dukes and barons, with the King at the head of all things. That says nothing of the thousands of ordinary people who worked the land or followed their crafts through all the centuries, and who lie in their hundreds in the churchyard. They had no coats of arms by which to be remembered. And yet they are recalled, for these shields glow in their glorious heraldic colours as a memorial to those who farmed and worked in this parish, they were made and fitted by our own craftsmen.”

It would be interesting to know more of the craftsmen and craftswomen of Kettleburgh, exactly where they worked over the centuries and how much they depended on the river.

The roof beams and shields at Kettleburgh.’ Note that there are ten shields. The one least visible at the bottom left of the picture is the shield of King Henry III who possessed the manor from 1241 until 1265

– – –

Time to move on. For a church that I had considered might not qualify, the Church of St Andrews at Kettleburgh proved well worth the visit. We will exit the churchyard through the gap by which we entered – between the cottages.

Leaving the churchyard of St.Andrew, Kettleburgh through the gap between the cottages.

– – –

In part 1 of this three-part series we followed the Deben from its sources near Mickfield and around Aspall, through Debenham and Cretingham as far as Brandeston. Now we have extended our exploration past Hoo and Kettleburgh where the Deben valley shows signs of widening. Perhaps it is important, now, to remind ourselves of the topography of the valley as it unfolds between Kettleburgh and Melton.

Even on the map there seems to be an awful lot of water! In reality, from recent events with the weather, we know that there is an awful lot of water and from studies of medieval history we are safe to assume that there always was. We are told that the Trinovantes, an iron-age Celtic tribe, made their way north to Debenham by water and we know that the Anglo-Saxons made their way to Rendlesham by boat so there must have been more water than there is now. If we go back far enough, we find the River Deben was part of the Thames Estuary but that is long, long before the birth of Christ and, in consequence, even longer before the building of the Churches of the Deben.

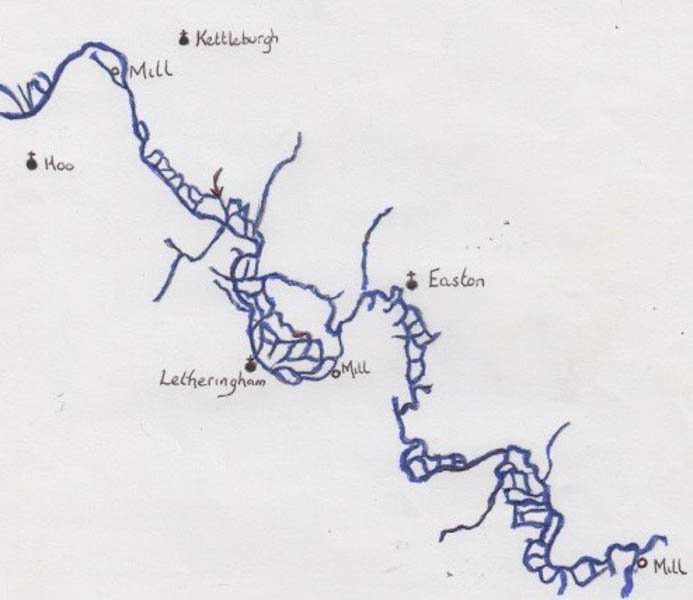

Maps show lattices of water courses through the Deben valley but the main waterway has always provided sufficient flow to support watermills judging by their existence at Kettleburgh, Letheringham, Wickham Market and Ashe to name but a few.

Find the main river! A doodle chart showing the lattice of water around Letheringham and Easton and north of Wickham Market. If you think this looks complicated you should see what it looks like between Ufford and Bromeswell! Not to be used for navigation !!

– – –

The next ecclesiastical visit along the Deben is correctly called The Priory Church of St Mary at Letheringham. The current church is the nave of the church of an Augustinian priory which was founded in 1194. The church has suffered much decay in the past to the point of losing its chancel and the approach to the nave and tower has been almost subsumed by the farm buildings of Abbey Farm. It really is ‘off the beaten track’ but clearly cared for.

The Church of St Mary, Letheringham – as seen when travelling north from Letheringham to Hoo on the road beside the Deben – one might be forgiven for thinking that this church was in a farmyard!

– – –

I have to admit that Letheringham was news to me despite my being married in Thorndon in 1969, being a frequent visitor to Suffolk over the next decade and then in 1979 coming to live permanently in south Suffolk. How could I have missed this archaeological jewel, especially when it is less than half a mile north of Easton Farm Park and, wait for it, just over 600 yards from Easton Grange, the venue for our youngest daughter’s wedding reception in 2013 (and our son-in-law’s, of course)? In this respect I am encouraged by John McCarthy’s introduction to ‘Life on the Deben’ in which he says that ‘despite living in Woodbridge’ and having ‘sailed on the river for many years’ the making of the film with the same name was for him a ‘Voyage of Discovery’ as he had hardly ever explored the upper reaches with its many beautiful hidden stretches of river.

The upper reaches of the River Deben in all its glory in 2013. Six hundred yards across the valley to the right is the Priory Church of St Mary and thirty yards across the grass to the left is Easton Grange.

– – –

The guide to the Priory Church of St. Mary tells us that there was a church in Letheringham in 1086 at the time of the Domesday Book but there are two schools of thought as to its whereabouts. There are those who believe that the existing church was preceded by another ‘about a mile away’ which ‘served the parish until its demolition sometime in the 17th century’. No trace of such a building has been found but, of course, it may have been a very simple wood-framed wattle and daub structure in contrast to the stone structures of the 12th century which we know today. Numerous skeletons have been unearthed near Letheringham Mill and the Old Hall. If there was a church in that area, then it would have been very close to the river and it would have co-existed with the Priory Church of St Mary.

The other school of thought is that the Priory was developed around the already existing church, on the site of the building we see today.

When the Priory was in its prime it was approached through a south-west gatehouse which still stands although its arches are bricked up, it has a modern roof and the guttering and drain-pipes are plastic, so interesting but not particularly photogenic. Today the church grounds are approached through an old metal gate beside a farm building. At the gate there is an illustrated and informative sign which tells us that the Priory was a cell of the Augustinian Priory of St Peter and St Paul in Ipswich and that the canons sent to St Mary’s were probably old, ill or ‘naughty’!

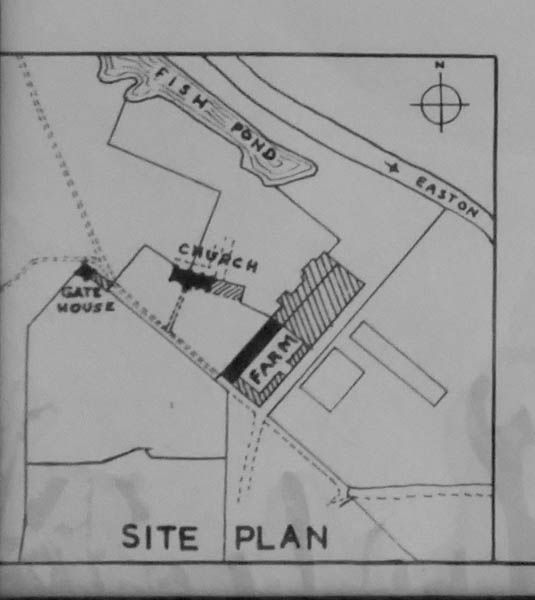

Site plan as seen in the corner of a plan of the church on display in the porch. The gate to the churchyard and the information board are next to the building labelled ‘FARM’

– – –

In line with Henry VIII’s break from the Roman Catholic Church and his Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Priory was dissolved in 1537. This was nine years after Cardinal Wolsey dissolved the parent Priory in favour of founding his college which, of course, did not get beyond the famous gate.

Following dissolution, the Letheringham land was granted to Sir Anthony Wingfield, already the owner of neighbouring land and Captain of the Guard to Henry VIII. The church then began to deteriorate, mainly at the hands of pilferers and vandals and not so much, as one might expect, at the hands of ‘Smasher’ Dowsing and his agents. By 1750 the church was ‘in a ruinous condition’ but at least the monuments were in reasonable condition. In 1780 a record was made to the effect that the “Roof…..and much of the Walls entirely down. Roof of the Chancel was standing, but all the monuments so broken and battered to pieces that the Havoc must have been purposely committed”

In 1789 the parish was ordered by church authorities to ‘put the building in decent order’. The guide continues by saying that ‘Sadly, instead of repairing it , the churchwardens gave a contractor the entire fabric of the chancel (all 56 feet of it – it was longer than the nave because it was a Canons’ Chancel – traditionally the chancel was for use by the clerics and the elite and the nave was for use by the public) and its contents, including the remains of monuments to do with as he would, as long as he repaired the nave.

The contractor is said to have crushed many stone ornaments and memorials and to have used the material for road making ballast. What he didn’t use he dumped against the west door which is now only two-thirds visible.

The Church of St Mary, Letheringham, as it is now.

– – –

Inside, the church is simple. There is a particularly well-proportioned Norman arch in the north wall through which the canons would have accessed a cloister. There is a modern cabinet in which the remains of some of the Wingfield monuments are displayed and there are rescued brasses hanging either side of the altar.

The Norman archway (12thC) in the north wall at Letheringham

– – –

The simple, bright and peaceful nave of the Priory Church of St Mary, Letheringham

– – –

We leave the simple nave, as we entered, through the 17th century brick porch, pausing to examine a picture of Letheringham’s Dad’s Army before venturing out into the cold.

The Letheringham Home Guard, complete with mascot, as remembered in the church porch.

– – –

It is good to know that the area was so well guarded, but I reckon any invading force would have had trouble finding the place, especially with no road signs.

The River Deben flows southward beneath Sanctuary Bridge just to the east of the Priory and then enters Easton Farm Park where it passes through two or three parallel channels before reaching the hamlet of Letheringham with its row of riverside cottages. Then it turns east toward the Letheringham Watermill and the Old Hall near which a church older than the Priory may have stood. Then, it heads north to Easton.

In contrast to Kettleburgh, Easton is shown on the OS Explorer map with the tankard signifying the pub, the White Horse, as close as one can get to the sign for the church-with-tower. In real life, in 3D if you like, one passes the front of the pub to access the footpath up to the church porch, and vice versa – an excellent arrangement.

The White Horse at Easton. Look very carefully lest you think that fifth chimney has an odd shape – it is, in fact, the hexagonal upper part of the tower of All Saints Church.

– – –

The path up to All Saints’ Church, Easton passes alongside a crinkle-crankle wall which abuts the south-west corner of the tower. The wall, which was built as the boundary to the Easton Park estate was 2.5 miles long when it was built in 1830 and it is reputed to be the longest of its type in the world. Most of it still stands but, today, the longest continuous section is ¾ mile. A hit and run driver did it no favours in 2013. The wall is said to have been built to enable the Duke and Duchess of Hamilton to walk to church unobserved, but this is unlikely as it was commissioned by the Hamiltons’ predecessor and maternal cousin, the Fifth Earl of Rochford who died, unmarried and without an immediate heir, in 1830.

The crinkle-crankle wall beside the path to the South Porch of All Saints at Easton, still suffering the after effects of no-mow May. As an aside, Country Life described crinkle-crankle as one of those ‘wonderfully euphonious reduplicatives that appear willy-nilly in the English language’ but they also called the river the Debden. In fact, crinkle-crankle is not so willy-nilly – it is derived from the 16th century English word -crink – meaning twisting or tricky.

– – –

All Saints Church at Easton. It is clear to see from the roof-lines that this was built with a distinct nave and chancel. Inside they would have been separated by a rood screen and a step or two up into the chancel but all that was changed by the dreaded Dowsing.

– – –

The Church of All Saints at Easton was not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 although there was a church at Martley just half a mile north. The current building dates from the late 13th century. The octagonal top to the tower was probably not added until the 15th century. Although the Church appears to have two southern porches, the one to the right (east) of the picture is ‘faux’, a 19th century addition comprising a vestry. The ‘entrance’ arch is blind and the door is out of site on the right side. It was clearly built to match the genuine southern porch, aesthetically, anyway.

Inside the church, the neatly constructed boxed pews impress, evidently (according to a tablet in the base of the tower) ‘new Pew’d at the expence of William Henry, Earl of Rochford, Who also built the Gallery in 1816”. The gallery was pulled down in 1887 on the orders of the Duke of Hamilton who thought it was an ‘eyesore’.

The rood stairs are clearly visible in the north wall of the nave but, of course, there is no other evidence of the rood screen and the rood loft.

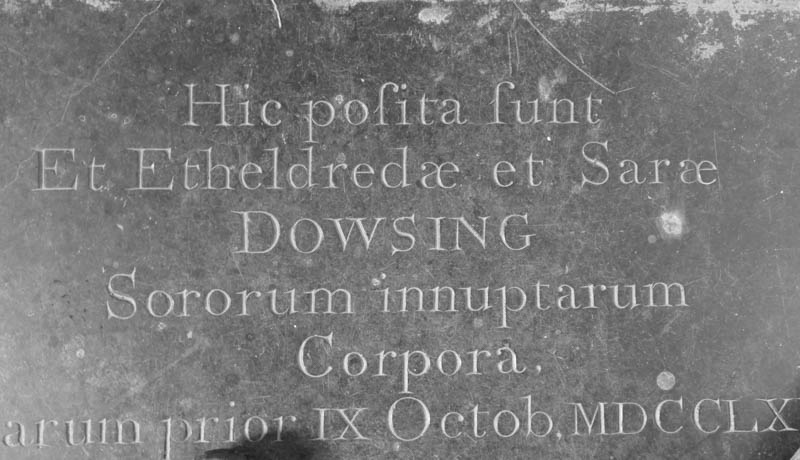

Unique amongst the pews are the Wingfield pews (for the family Wingfield who were Lords of the Manor in the 17th century – is the name ringing a bell?) situated at either side of the altar but also very close to a ledger slab for members of the Dowsing family who resided in Easton.

There is a comprehensive church guide written by Robert Warner which includes the history of Easton.

Inside the Church of All Saints, Easton. The boxed pews in the nave are very neat. The rood steps are clearly visible in the north wall of the nave, slightly to the left of the centre of the photograph

– – –

Extra special pews for the aristocrats enabled them to sleep, eat, and even have small fires during services. The carpet seen in the bottom left-hand corner partially covers the Dowsing ledger slab

– – –

Part of the Dowsing ledger slab ‘Here were laid the bodies of Etheldreda and Sara Dowsing, unmarried sisters – 9th October 1760 – or words to that effect – it is a long time since I did Latin O-Level. This slab was laid just over a century after their ancestor, William, had been stripping the churches of anything popish. Perhaps all was forgiven by 1760

– – –

I have searched Easton for some kind of non-Conformist chapel but have found no sign of such. Perhaps the dominance of the ‘big house’ in the community made such an enterprise too tricky to consider.

It is time to leave Easton and make our way past Glevering Hall, Glevering Mill, Glevering Bridge and Glevering Hall Farm (strangely no Glevering Church) toward Wickham Market with its distinctive spired church, situated at the top of a hill and visible for miles around.

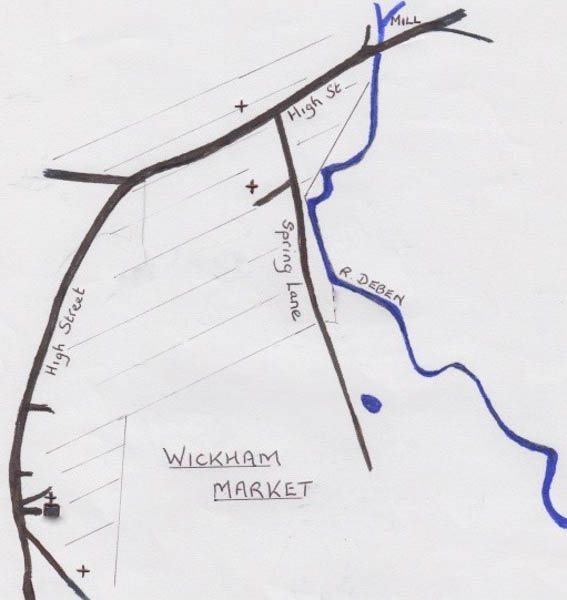

The river passes through Deben Mills at the north-eastern extremity of Wickham Market and one gets the impression that, as in Kettleburgh, the church is a considerable distance from the River Deben. Nevertheless, the same principle applies – many of those who have worked with or near the river over the centuries will have used this church.

The River Deben arrives at Wickham Market at Deben Mills which lies at the north-eastern extremity of the town. The water was over the top of the archways and into the buildings following storm Babet in October 2023

– – –

The river passes under the main road which goes into Wickham Market, then travels south toward the very low-lying outskirts of the village in the vicinity of Spring Lane; it then takes a turn toward the south-east and wanders off casually in the direction of Campsea Ashe, as if to ignore Wickham Market, although, interestingly, the National Gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland 1868 described it as a ‘village situated on the bank of the river Deben’. At this northern end of the village, it is only a matter of yards to the riverbank and the Deben forms the parish boundary first with Hacheston and then with Campsea Ashe.

Wickham Market ‘on the bank of the River Deben’ – well, yes – very, very close to the bank in some parts of Spring Lane but remember that the parish church and the village centre is at the top of a hill and Spring Lane is at the bottom. The mill is depicted at the top of the map and two chapel sites are seen in the low area of the conurbation (hatched). The other chapel (Independent Congregational) which still exists but as apartments, is at the top of the hill not far from the parish church.

– – –

A timeline included in the Wickham Market Heritage and Character Assessment in 2017 shows that in 1780 an ironworks was set up at this northern end of the village; it employed 100 men. This might account for the fact that, also at this northern end, in 1810 there was a Dissenters meeting which resulted in riots. We are told that by 1812 the Wickham Market Protestant Meeting house was opened and used as such until an Independent (Congregational) Chapel was built in Loudham Lane in 1872. Further enquiry as to the whereabouts of such a Meeting House proved fruitless but I did find reference to one Christopher Hill saying that in the Primitive Methodist magazine of 1837, page 110, there was information about the opening of seven Primitive Methodist chapels in the Wangford circuit (which included Wickham Market).

In Wickham Market, we are told, a large and eligible room was ‘hired and fitted up’. The opening services for Wickham Market Primitive Methodist chapel started on 10th June 1836. Attendances are said to have been large. As far as I can ascertain this ‘eligible room’ was in a building on Spring Lane at a site now occupied by modern housing on the corner of Spring Lane with Barhams Way – it closed before 1874. In 1932 the Primitive Methodists nationally rejoined the Wesleyan Methodists from whom they had originally split in 1807 in an attempt to become more lay orientated and evangelical. The Genuki geneology website tells us that the Primitive movement had proved ‘particularly successful in evangelising agricultural and industrial communities at open meetings’ and, of course, in the 19th century Wickham Market had both.

Just across the High Street from Spring Lane there used to be a chapel known as The Gospel Hall. Wikipedia Commons tells us that this was a 19th century prefabricated building, initially used by the Salvation Army and then used to billet men during WWI. From the 1920’s it was used as a Gospel Hall which is a collection of non-denominational evangelical believers. I have been unable to find an exact date for its closure, but it was demolished in 2013 in order to make way for housing.

The Gospel Hall in the High St., Wickham Market 1920 -2013 Image from <Geograph project> collection, acc. to Adrian Cable & licensed under <Creative Commons>)

– – –

All Saints’ Church in Wickham Market stands off the market square at the top of Snowdon Hill. Its octagonal tower and spire total just over 137 feet in height so that the spire is visible for miles around including, it is said, from the sea, although I have never put that to the test either in practice or through geometry.

The octagonal tower and the spire of All Saints, Wickham Market viewed from the churchyard

– – –

Roy Tricker, who wrote the twenty-page guide to the church, tells us that octagonal towers, octagonal from the base that is, are rare and this is the only one in Suffolk. At its base the walls are at least four feet thick – there are no buttresses outside to help support the structure. Building of this church began between 1300 and 1340 and there is documentation of the vicar of Hacheston giving half a mark (6s 8d) towards the building of the ‘new tower’ in 1384. Wickham Market’s own incumbent doubled that, giving one whole mark toward the exercise.

Showing the impressive thickness of the tower walls. The door to the left leads into the tower porch

– – –

The immediate impression on entering this church is one of modern adaptation. There are glass doors inside the entrance at the west door with evidence of skilled modern carpentry. The pews have been removed and replaced with comfortable chairs which may be used either for worship or at tables in the ‘pop-up café’ in the western end of the nave. Part of the ancient panelling near the organ bears discrete notices to ‘Mind the step’ and ‘Toilet’.

The roof and Decorated windows of the south aisle. Two of the 17 wall posts are shown. They probably started life as apostolic figures but were defaced in the 1640s by William Dowsing et al.

– – –

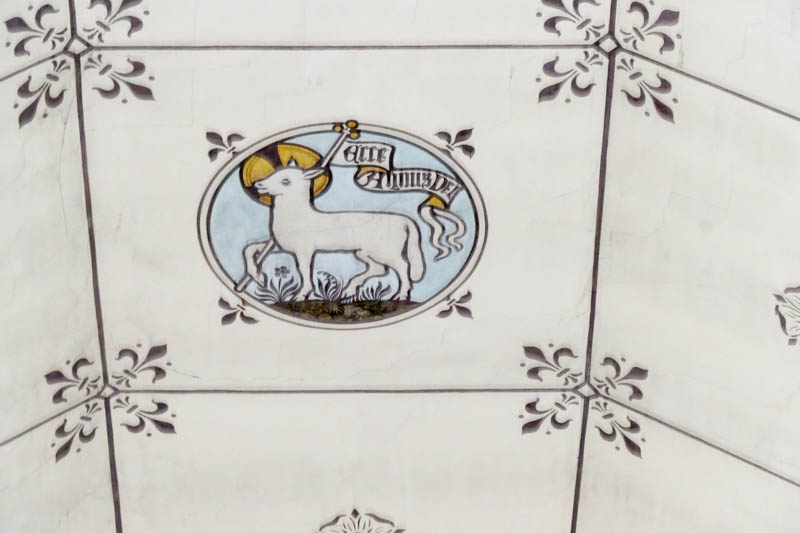

These adaptations complement rather than detract from the fine tracery of the Decorated windows, the 15th century roof of the south aisle with its defaced wall posts, the height of the chancel arch and the panelled (19th century) roof of the chancel with its singular Agnus Dei panel.

Agnus Dei – the Lamb of God – beautifully portrayed in a panel of the chancel roof at the Church of All Saints, Wickham Market. I admit to some self-indulgence here; not only is it beautiful and relaxing to admire, but my school cap carried a similar image in white on black and my medical school scarf carried the fleur-de-lys in white on blue. Consequently, I feel some connection!

– – –

Anyway, time to move on to Rendlesham; but wait, yes, wait: just beyond the church there is a road called Chapel Lane. In my experience nobody calls a lane ‘Chapel Lane’ unless there is a chapel there, but a few enquiries produced no helpful information. ‘Yes, there was a workhouse down there but don’t know of any chapel’, they said.

Then I went onto ‘street view’ with Google maps and, ‘walking’ down the lane I saw a building with a couple of memorial stones in an archway on its front elevation. Otherwise, it looked rather like a large house built with buff-coloured bricks and with wide sash windows – difficult to date – ? late Georgian/early Victorian. Then I went back to the aforementioned timeline which referred to an Independent (Congregational) Chapel being built in Loudham Lane in 1872. Well, Chapel Lane leads directly to Loudham and before the chapel was built there would be no reason to call it Chapel Lane – so probably safe to assume they are one and the same.

But something doesn’t quite fit because this ‘house’, now called Waterloo House, is described as being built in 1815. I wonder, therefore, if this was the mysterious Protestant Meeting House and that perhaps in 1872 it formally adopted Congregationalism. The alternative is that someone got it wrong, it was built as a Congregational chapel in 1872 and the Protestant Meeting House remains a mystery. Anyway, the chapel closed in 1985, thirteen years after the Congregational Church of England and Wales formally merged with the Presbyterian Church of England to form the United Reformed Church – a time when some Congregational churches chose to remain independent at some risk of their demise.

The former Congregational Chapel, Wickham Market as it appeared, on the housing market, in 2017. It was built in 1815 (or ??1872) and closed as a chapel in 1985. It goes some way back off the road, has a shallow slate roof and deep, carved eaves (the carving is not easily seen in this reproduced image.) The memorial plaques are in the archway on the right. I imagine the chapel would have had a large gallery and that it would have had seating for 250 to 300 people. The building is now divided into apartments.

– – –

Well, that was an interesting find – time now to travel further south through the Deben Valley but not before making the reader aware of another reference I found in the Wickham Market Heritage and Character Assessment of 2017. To quote ‘In 1937 there was major flooding. The water was 10 feet deep over all the land between the hill at the top of Wickham Market and the opposite hill’. It is not clear what is meant by the ‘opposite hill’ but I imagine it is Campsea Ashe – the other side of the Deben Valley. Ten feet – that’s something.

The River Deben takes a south- easterly course from the northern end of Wickham Market, takes one look at Campsea Ashe (as it is today – Campesia as it was at the time of the Domesday Book) and turns southward toward the Loudham Estate. The Deben is the nearest river to the village of Campsea Ashe but the church is nearly a mile away – too far.

The river drains into a decoy pond before dropping over a weir and passing Ashe Abbey and the remains of an Augustinian priory – St Mary’s Priory of Augustinian Cannonesses, founded in 1195 by Theobald de Valoines for his sister, Matilda of Lancaster, who was a distant relation of Edward I – but so is Josh Widdicombe! It is said that the Priory became a fashionable resort for women of high birth. The onesuffolk.net information goes on to say that ‘There was also a small college of Cannon attached to the nunnery and it became quite a successful priory. In 1249 it is recorded that the ‘monks of Campes obtained a free warren from Esce’ (Esce being an ancient word for Ash and warren being a freedom to breed game or poach). The mind starts to boggle as to what made ‘a successful priory’.

A large low-lying area was set aside to be flooded as a fishing lake adjacent to the Priory, enabling the residents of the Priory to fish and eat. The river was dammed in two places and the decoy pond was the result. The course of the river was changed again in 1204 using quills to drain the water when the river was diverted. Hence the name of Quill farm which lies on the banks of the river just west of Campsea Ashe. The mill at Ashe / Loudham was functional from those times until WW2 but ‘has long since disappeared.’ There is no mention of a church but there must have been a chapel within the Priory.

The river continues southward from the Priory, over another weir and into the grounds and farmland of Naunton Hall. This area is ‘archaeologically sensitive’ showing, as it does, evidence of high-ranking Anglo-Saxon inhabitation including the foundations of a possible temple for pre-Christian worship. The Venerable Bede wrote in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, circa 731 AD, that King Redwald, the Anglo-Saxon king who died about 625 AD and was buried at Sutton Hoo, had a temple in which there were both Christian and pre-Christian altars. It is thought very likely that it was here in the Naunton Hall farmland, just about 500 yards from the Church of St Gregory the Great at Rendlesham, or even on the site of the church as it is now.

The proud Church of St Gregory the Great at Rendlesham

– – –

Proud but lonely are the feelings I get when visiting this church. There was a church here at the time of the Domesday Book but this building is mainly 14th and 15th century. The loneliness of the site might well reflect the fact that the Saxon township was wiped out by the Black Death. The tower, which is the first part of the church which one sees from the lane, stands proud and strong with its eastern buttresses giving an impression of extra width. It is lonely – there is nothing else about – apart from the old rectory next door and the occasional vehicle in the ‘lay-by’ outside – the only place to stop on this winding lane in order to ‘take one’s sandwiches’ – today it was the van of a drain clearing company – a rival for Dyno-Rod. They must have wondered what I was at, wandering about, diving in the undergrowth at the edge of the graveyard, taking photographs in this lonely but historic place.

The church seems in a good state of repair, but the occasional sign of wear and tear gives sight of the tremendous amount of labour which went into the building – imagine the work and artistry required to make all these small flint tiles in order to give the chequered effect at the base of the tower – a process known as flint knapping.

Flint- knapping: Each flint ‘tile’ measures in the order of 5 x 6 cms and is about 1cm thick

– – –

The south porch has an upper floor and the nave and chancel show delightful clear Perpendicular windows, very pleasing to the eye. The roof is clearly lower than the original as evidenced by an old roof line on the eastern wall of the tower and the presence of a sanctus window slit through which the bell-ringer could view the chancel at the time of mass.

The south wall of the Church of St Gregory the Great with its two-storey porch and beautifully sculpted perpendicular windows in both the nave and the chancel.

– – –

The upper room of the porch is accessed through an ancient door in the south wall of the nave through the keyhole of which I was able to see a bell rope – or was it a rope to help in the ascent of the steep steps?

Inside the church there is a relaxed and homely feel as the pews are a pastel grey and the walls are colour washed in pale terracotta. The Perpendicular east window proved irresistible for a photograph, such was its Florentine intricacy.

The light was all wrong for a photograph of John Caperon’s full size effigy lying in a tomb on the north side of the chancel. He was the vicar here in 1349 – he paid quite heavily (40 shillings) for the privilege of being buried in his own chancel.

The door to the upper room of the porch and the rope end seen through the keyhole. I just love the pale terracotta colour wash which gives such a relaxing feel to the whole church

– – –

The Perpendicular East window at the Church of St Gregory the Great with its fine tracery, evidently sculpted in Florence.

– – –

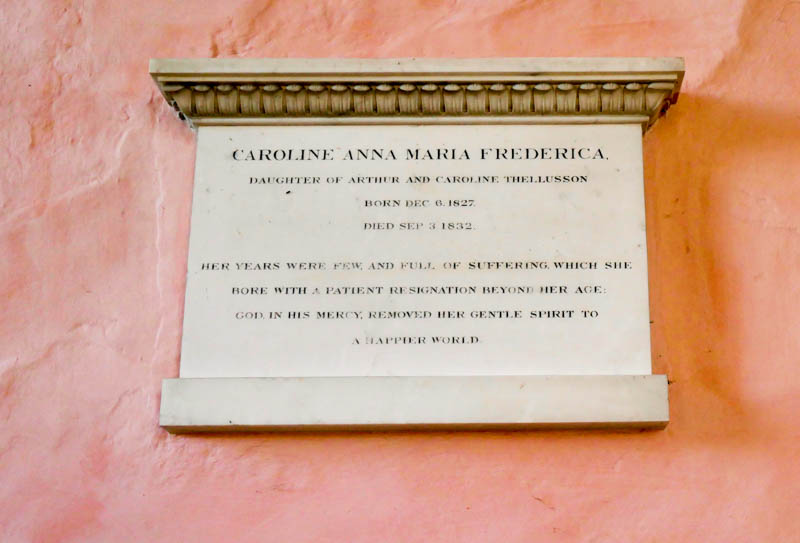

Obviously at one time the Thelusson family were the local dignitaries as there are several memorials to them – however, there is one which brings a tear to the eye as the subject was a young child. Of Caroline Anna Maria Frederica Thelusson who died aged four in 1832 it is recorded that

‘Her years were few and full of suffering which she bore with a patient resignation beyond her age.’

The memorial plaque to four year old Caroline Anna Maria Frederica Thellusson

– – –

Before we leave – we must remember to look up at the extensive arch braced roof. Its simple wall posts did not require the destructive attention of Will Dowsing or his agents.

The arch braced roof at the Church of St Gregory – such simple craftsmanship

– – –

The village of Rendlesham is served by a second church – St Felix – which lies in the heart of the ‘new’ village. As a building it started life as the church for the USAF base during the Cold War. However, St Felix is approximately a mile from the river – too far for our purposes.

The next community with a church near the River Deben is the small village of Eyke. Since 1993 the church guide has been merged with a guide to the village; it was written originally by Patrick Ashton in 1981. He used his introduction to explain that:

‘Much of our information comes from the handwritten exercise book by Archdeacon Darling (Rector 1893 – 1938) who was such an influence in the village. It was not until the ink had nearly faded that the pages were photographed, and some are now indecipherable.’

The Archdeacon, the Venerable J.G.R. Darling was a skilled woodworker and in the 1930s he ran classes for anybody interested. Much of the church furniture, including the font cover, the reredos, the screen, some chancel pews and the pulpit was made either by the Archdeacon or by his woodworking pupils.

The guide says that there was no mention of Eyke in the Domesday Book but there is a record of a church at Staverton which was part of the Manor. There are records, also, of two churches in Bromeswell, of which more later – when discussing Ufford.

The guide starts its description of All Saints in Eyke in a very self-deprecating manner. It reads:

‘A good many churches look their best from the outside but with us it is the opposite. We have no magnificent profile, no tower, thank goodness – there was one once but it fell down. Neither do we stand on a good sight in a pretty village. We are no more than a barn, taking our place amongst the houses that have come and gone around us over the many, many years………’

The Church of All Saints in Eyke – supposedly no more than a barn – but it used to have a tower – in the middle, just behind that yew tree.

– – –

It is thought that the tower collapsed in the 15th century but strangely there appear to be no accounts of such a happening. It is, perhaps, surprising that it collapsed, bearing in mind the apparent strength of the Norman (12th century) arches which supported it.

The impressive Norman arches which once supported a central tower at the Church of All Saints in Eyke

– – –

There is a carved memorial in the chancel stalls remembering H.R. Cholmeley. Arthur Mee suggests that it was carved, [probably by the Archdeacon], in memory of his son ‘who drowned in the river close by’. With a different surname it is more likely to have been his grandson, but I might stand corrected. It is complicated by the fact that the Archdeacon’s father was the Rector in Eyke for 34 years in the 19th century. In 1915, when H.R.Cholmeley died, the Archdeacon would have been 48 years old. I have not been able to ascertain the age of the person who drowned or, for that matter, the circumstances of the accident.

Hanging on the north wall in the nave is an ancient key (or, to be precise, a replica of a key). The real key is in the British Museum; it is at least 500 years old with wards cut in the shape of the letters IKE, which was one way of spelling Eyke (meaning oak) in the Middle Ages.

Referring back to the extensive guide I found the following piece of information:

‘A wooden building near Mr Larrett’s house was used by the Baptists for services for a number of years.’

With Eyke being a compact village, it is likely that Mr Larrett’s house was no further from the river than All Saints’ Church, but I don’t think a non-specific ‘wooden building’ warrants inclusion in our Churches of the Deben. Purists might try to disagree bearing in mind the well-known gospel text saying ‘Where two or three are gathered together…..!’. On balance, we have to assume that the Baptists of Eyke did not quite get round to building a chapel. Phew! Because the numbers keep going up. It seems a long time since we left Hoo.

Across the Deben valley from Eyke, and closer to the river, is Ufford. The distance between them is just over a mile. There are 28 listed buildings in Ufford and many of them are situated close to the Grade 1 listed Church of St. Mary of the Assumption which dates from the 11th century. The church guide says that the lower four metres or so of the north wall date, probably, from the first half of the 11th century. It goes on to explain that four local churches were ascribed to Bredfield or Bromeswell in the Domesday Book whilst Ufford, like Eyke, was credited with none. With there being no evidence of a second Anglican church in Bromeswell one has to assume that one of the local churches was Ufford’s – who knows?

The Church of St Mary of the Assumption, Ufford

– – –

As with many other Anglican churches, a major part of the building of this church, including the tower, took place between 1400 and 1500. The church tower presents its fine features full on to visitors as they approach with centuries’ old, thatched cottages on the left and a high brick wall on the right.

Then a degree of incongruity kicks in shortly before the church gate where the whipping post and the stocks stand only a yard or two away.

The stocks and the whipping post by the Church gate in Ufford

– – –

However, there is a quick return to the eccliastical as a glance to the right shows the pure architectural beauty of the porch, built to abut the south wall in 1475 or thereabouts. The church guide describes it as ‘an essay in the flushwork and knapped flint’ so typical of Suffolk churches and draws attention to the exquisite detail of the plinth.

The porch in Ufford – ‘an essay in flushwork and knapped flint’

– – –

A quick look around the back of the church would be a mistake – although frequently such a look reveals modern paraphernalia such as wheelie bins and wheelbarrows – not here. A slow look would be much more appropriate, giving time to identify the herring bone and zigzag features which are indicative of Saxon stonemasonry which was involved in the building of this wall a thousand years ago.

A slow look at the north wall in Ufford gives an opportunity to identify the zigzag and herring bone patterns indicative of Anglo-Saxon stonemasonry. Look carefully between the nearest two buttresses.

– – –

Inside the church there are many fine features to which only the guide can do justice, researched as it has been by that expert in things eccliastical, Roy Tricker and the Suffolk historian, the late W.G. Arnott. However, no recorded visit to The Church of St Mary of the Assumption should finish without reference to the unique font cover and the hammer beam angels.

The carved font cover is eighteen feet high with the symbolic pelican at the top and tiers of niches and finials below. It so impressed the iconoclastic Mr Dowsing that it was spared his destructive tendencies in 1644. Not so, the angels and cherubim (which is the plural of cherubim, before you imagine asymmetry in the roof) at the ends of the hammer beams; they were replaced in the last decade of the 19th century, having been carved in Oberammergau. (Don’t ask me to explain the difference between angels and cherubim – I suggest googling it and you might end up a little wiser – or not, as the case may be!)

The magnificent eighteen-foot font cover at Ufford

– – –

A fine pair of Oberammergau-carved angels (or cherubim). I swear they moved whilst I was taking this photograph but so did the pew which I was using for support.

– – –

Before leaving Ufford, a shortish walk to the northerly outskirts of the village, on the Yarmouth Road near Byng Brook will reveal a building, now a private house, which was erected as a chapel for the Primitive Methodists in 1860. The date is carved in large numbers above the arch of the front door. It became Wesleyan Methodist in 1889 but ninety-nine years later it was obviously in a state of conversion.

Ufford Primitive Methodist Chapel, Ufford. Photo by Keith Guyler 1988: Licensed to Christopher Hill 11/08/2015. The opening of this chapel in May 1860 was recorded in the Primitive Methodist Magazine of August 1860.

– – –

The nearest church to Ufford in our quest to get to Melton ‘by church’ is just under a mile away in a south south-westerly direction. It is the Old Church of St Andrew, Melton, aka Melton Old Church. It is situated about 100 yards from the river. It has not been used as a place of worship since the late 19th century when the Victorians decided to build a new church, nearer to the expanding population of Melton, but 500 yards from the river and with little space for burials in its grounds. Melton Old Church had massive amounts of room for burials so it became the cemetery church and was adapted as such by demolition of the chancel and the building of an apse which must have looked really good until someone added a square block to it. The building is now owned and administered by members of the Melton Old Church Society who use it for meetings and concerts. The situation is remote and peaceful with the Mill House to one side, a decoy and nurseries to the other, a huge graveyard to the fore and the river behind.

The view over the valley to the south side of Melton Old Church of St Andrew

– – –

Melton Old Church in the setting sun

– – –

The nicely shaped Victorian apse. Fortunately, its square extension is almost hidden from view

– – –

If we continue beyond Melton Old Church by road (or lane, to be precise) we will reach the village of Melton with its ‘new’ St Andrew’s Church, built in 1868 along traditional lines. If, on the other hand, we return to Ufford, partake of a jar in the White Lion and make our way across the valley, we will come across Bromeswell. The valley between Ufford and Bromeswell represents the ‘great divide’ where landlubbers must decide which side of the river to take first, a decision which will have to be taken before proceeding with part 3 of this series unless, of course, we zigzag by boat from one side to the other of the now estuarine Deben.

The lane from the White Lion in Ufford to the village of Bromeswell presents the penultimate opportunity to cross the valley by road, the last being the Wilford Bridge at Melton. The names ‘Low Farm’, ‘Bridge Road’ and ‘Sink Farm’ give a clue to the terrain. I lost count of the bridges but there are five at least.

The Church of St. Edmund at Bromeswell would be an appropriate place to end this second part of Churches of the Deben. It is dedicated, along with 20 others in East Anglia, to the patron saint of East Anglia. Born in 841 AD., he was King of the East Angles (Norfolk, Suffolk and the Isle of Ely) but he was put to death for his Christian beliefs in 869 AD. by a Danish ‘firing’ squad who tied him to a tree and shot him with arrows. This is all in the excellent guide book put together and revised in 2023 by – you’ve guessed it – Roy Tricker and William Notcutt.

The Church of St Edmund at Bromeswell is hidden from the casual observer

– – –

The authors tell us that there was a church here in 1086 and that the current stone walled nave was built in 1100 by the Normans. The archway housing the door from the porch into the church is certainly Norman. The perpendicular windows in the nave probably date from the early 1400s, the tower and its flintwork from the later 1400s and the Tudor brick porch from the late 1400s / early 1500s which is about the same time as the pews inside which are now equipped, I notice, with 20th century cushions (for the people sitting nearest the walls, at least).

The church sits on a mound; it is approached along an unmade lane and does not impose itself on to the casual observer. However, to the purposeful visitor, or to worshippers, it fairly exudes history. Just looking at the church from the southerly aspect raises observations and questions in one’s mind.

- Compare the small Tudor bricks of the porch with the less glamorous 19th century (actually 1845) bricks in the chancel.

- Has the roof of that porch been raised at any time? – almost certainly.

- How come there is a priests’ doorway arch typical of the early thirteenth century surrounded by 19th century bricks in the chancel wall? – is it a fake? No, it was carefully protected during the demolition of the old chancel walls and painstakingly inserted into the new wall.

- What lies beneath the limewash rendering of the south wall? – brown septaria which was the principal building stone of the Anglo-Saxons in this area.

Round the back, where it really is best not to look, there is a modern extension (1984) complete with late 20th century bricks and double-glazed windows.

The Tudor porch at the Church of St. Edmund

– – –

12th century priests’ door in 19th century bricks

– – –

Inside the church there is a finely carved font which was subjected to the puritanical purge of 1644. There is no record of such action in Dowsing’s Journal so it could be that the churchwardens carried out the desecration voluntarily, thus avoiding a visit from the man himself. Ufford, meanwhile, being less anxious to divest themselves of ‘superstitious images and inscriptions’, got two Dowsing visits.

The finely carved font defaced during the Puritanical purge of 1644

– – –

The authors of Bromeswell’s Church guide believe that the steep pitch of the simple single hammerbeam roof of the nave is indicative of it being ‘quite an early example’ of this impressive craftsmanship in wood. Each hammerbeam would have had an angel attached until 1644 but they were removed in the puritanical purge. Strange then that there are, today, seven pairs of angels flying in this roof.

The explanation lies with the Venerable Archdeacon Darling, the rector of Eyke, and with his aforementioned woodworking skills. In 1933 he took on St. Edmund’s, Bromeswell as an extra parish and decided that he would try to replace the missing angels with his own carvings. Regrettably he died in 1938 by which time only three of the angels had been completed. The most easterly pair and the southerly half of the next pair are genuine article Darling angels but the other eleven are made of fibreglass; they were installed during the incumbency of Revd Patrick Ashton who was the rector at Bromeswell from 1966 to 1987.

Inside the Church of St.Edmund at Bromeswell. The nave is just 15½ feet wide. The three wooden angels are too distant to be seen in any detail; even the eleven fibreglass angels seem to be trying to hide in this hammerhead roof. The organ pipes are vertical in real life!

– – –

Preparing to leave this place, standing outside the church, we are just 1½ miles from the ship burial site at Sutton Hoo; we are within half a mile of the heath where tens of thousands of troops amassed in preparation for the Napoleonic wars; we are 750 yards from the ever-changing, beautiful and mysterious River Deben. History pervades the atmosphere. A good place to reflect but an editor’s deadline calls, and I am now ‘churchapelled-out’, for now, anyway. We seem to have come a long way from Hoo.

I completed part 1 of this series by thanking various sources. I extend those thanks again. Just as I started this second part, an article in the East Anglian Daily Times brought attention to the fact that the Suffolk Historic Churches Trust had gathered together as many church guides as possible, digitalised them and placed them on their website. This is an amazing and valuable resource providing immense detail which I have not been able to touch on. I have purposefully avoided, for example, bells, commemorative windows and graveyards simply because they are such highly specialised or complicated subjects; all I am attempting to do with ‘Churches of the Deben’ is to encourage readers to be aware of each of these historic buildings and their artefacts and to visit and/or search out the information which interests them.

The Guides are available, without charge, via the SHC Trust website: shct.org.uk/guides-to-suffolk-churches

I might skip part 3 ‘Both Melton and Sutton to the North Sea’ and just read the guides!!

Dr Gareth Thomas MD., LL.M., FRCOG

Gareth Thomas retired as a local Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in 2010 and left the medicolegal world of Expertise in 2015. He and his wife Alison moved to Waldringfield from Rushmere Road, Ipswich in 2006, having previously lived in Nacton for nine years from 1979 – so they are getting to know the South Suffolk peninsula reasonably well! In 2007 Gareth became a founder member of the Waldringfield History Group and for ten years from 2010 he was Chairman of the Group. The end of his tenure of office coincided neatly with the publication of Waldringfield – a Suffolk Village beside the River Deben. The book was a combined effort on the part of all members of the small Group, but Gareth was one of the three members who took responsibility for the editing and management.

Never known for sitting about, Gareth may be seen around Waldringfield walking his dogs, on the water on ‘Blazer’ or crabbing with some of his younger grandchildren. He is also too well known (in his opinion) for his involvement in the village pantomimes.

For the last twenty-three years he and Alison have had a family home in the valley of the Vezere in south-west France where Gareth has been able to maintain a managed meadow and plant well over one hundred trees.